Forestry and Communities in Cameroon

Centre pour l’Environnement et le Développement, Friends of the Earth International, Cameroon

Author: Robinson Djeukam with the collaboration of J.-F. Gerber et S. Veuthey (ICTA-UAB)

.

Download case study as pdf-file.

.

Les concessions furent accordées dans l’espoir

que les compagnies «feraient valoir» le pays.

Elles l’ont exploité, ce qui n’est pas la même chose;

saigné, pressuré comme une orange dont

on va bientôt rejeter la peau vide.

André Gide, Voyage au Congo (1927)

.

.

.

1.2 The origins of timber exploitation

2.1 Power imbalance in extractive processes

2.1.2 Today’s macroeconomic actors in forest management

2.1.3 Accumulation by dispossession

2.2.1 Impacts on local populations

2.2.2 Conflicting languages of valuation

2.2.3 Unequal patterns of trade

3.1.1 Involvement modalities of local communities

3.1.2 Achieving sustainability: the illegality trap

3.2.2 Critical analysis of the FLEGT-Cameroon

4 DISCUSSION: CHALLENGES AHEAD

4.1 Defining and managing “legality”

4.2 Verification and credibility

.

.

This paper provides an overview of Cameroon’s logging situation – especially power issues, impacts on local populations, and the problem of illegality. The objective is to provide a new look at industrial logging in the region by using concepts taken from ecological economics and political ecology in order to stimulate a reflection that may foster a change. The article also focuses on legal devices supposedly aimed at mitigating negative impacts of logging activities such as the 1994 forestry law and the new Forest Law Enforcement, Government and Trade (FLEGT) process launched by the European Union. A positive point of the FLEGT is that it offers an opportunity for civil society to try to improve the legal framework – and its enforcement – regulating the logging sector operating in Cameroon. However, its economic rationale remains that which prevailed during the colonization period and continues today, namely to extract timber from peripheral poor regions and to export it to Europe. One of FLEGT’s major flaws is the presumption of the state’s respect for legality, and the entrusting to the state the monopoly of the verification process. Also, FLEGT does not challenge the legitimacy of Northern consuming patterns, nor does it question the legitimacy of private operators that originate in the North and that accumulate the lion’s share of the produced wealth. The concept of an ecologically unequal exchange is implicit everywhere in the present article. In our view, one way to achieve less unequal extractive processes is to resort to democratic deliberations – “participation”. This can only take place within more balanced power relations, a fact that is a clear from the contribution of post-normal science as well as from the idea of conflicting valuation languages.

Keywords: industrial logging, property rights, community forests, commodity chains, ecologically unequal exchange, cost shifting, corporate accountability, corruption, wood certification, fair trade, consumer blindness, languages of valuation, FLEGTVPA.

.

This article aims at providing a new reading of logging in Southern Cameroon by using concepts taken from ecological economics and political ecology in order to stimulate a reflection that may foster a change. In particular, it focuses on the “Forest Law Enforcement, Government and Trade” (FLEGT) process aiming at developing a “Voluntary Partnership Agreement” (VPA) between the government of Cameroon and the European Union on the matter of legal timber trade. However, because this kind of processes tends to restrict the discussion to a limited number of aspects, we find it crucial not to forget the bigger picture if our aim is to better understand what is at stake and what kind of strategies or public policies should be promoted. Accordingly, the paper provides a contextual overview of Cameroon’s logging situation – especially power and local impact issues.

.

1.1 The role of the forest

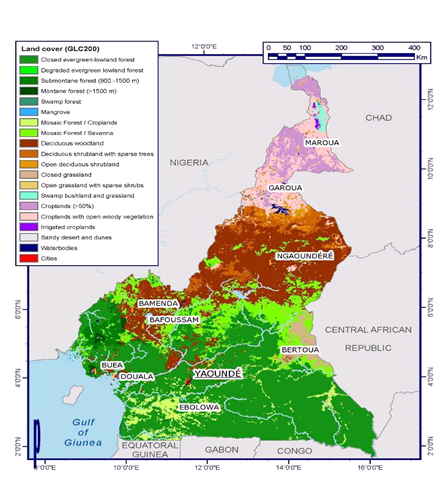

The Cameroonian forest covers an area of about 20 million hectares, which represents about 40% of the national territory. The importance of the forest is related to its multiple and sometimes conflicting uses and functions at local, national and global levels. From a conservation perspective, the forest constitutes a crucial reservoir of biodiversity, including many endemic species, and its contribution to climate regulation and other environmental services has now been established.

Cameroonian forests are the home to nearly four million persons belonging to Bantu ethnic groups as well as to the last indigenous populations of the African rainforest, the so-called “Pygmies”. Forest Bantu societies practice shifting or rotational agriculture, each family producing what is necessary by cultivating itself the different crops. A family field typically has a surface of 0.3 to 1.5 hectares and is exploited during two consecutive years before lying fallow during 3 to 10 years, sometimes much more. Trapping, fishing, and gathering still bring a large part of the food domestically consumed. While most Bantu are engaged in the production of cash crops, they often still lack health and education facilities, or basic infrastructure. There are also in Cameroon three large ethnic groups of indigenous “Pygmy” peoples: the Baka, the Bakola/Bagyeli and the Bedzan. All of them traditionally live from hunting and gathering in territorial and remarkably egalitarian nomadic bands. However they are increasingly adopting a sedentary lifestyle (agriculture) under the influence of multiple factors, such as massive deforestation leading to the loss of resources essential for their biological and cultural survival.

All of these peoples, to varying degrees, depend on forest resources for their livelihood. The forest represents a kind of huge free “supermarket” providing food, medicines, construction and equipment materials, as well as ceremonial elements. Their standard of living therefore closely depends on the quality of the forest. This access to natural resources and ecosystem services outside the market has been described sometimes with the words “the GDP of the poor”. Today, all these populations generally experience conditions of deep poverty, both in money terms and also in terms of direct access to resources. This phenomenon started with the arrival of the Europeans: first tradesmen looking for slaves, then colonists imposing labour obligations, taxes, and extracting natural resources in favour of the metropolis (timber, plantations, oil and mining). Before that happened, it can be argued that local populations were not “poor” as they adapted to their surrounding natural wealth, usually without undermining it.

.

1.2 The origins of timber exploitation

From a macroeconomic viewpoint, the exploitation of timber started during German colonization; took off after Second World War II, and intensified at the beginning of the 1990s. Timber thus became the second most important source of export income, after oil. The conflictive potential of the forest arises from the high profitability of its timber resources in a context of weak state control. This tends to drive loggers to act in contravention of their obligations, using corruption and other illegal practices, against the interests of the other forest users who complain accordingly. The resulting degradation of the forest tends to impoverish local populations. This is why the concept of ecologically unequal exchange will be implicit in the discussion throughout the article. The notion refers to a typical feature of the Cameroonian wood filière, or commodity chain, namely an extractive and export process characterized by the shift of negative environmental and social impacts onto forest communities and by the appropriation of wealth by Northern industries. A central question of the paper is to what extent the FLEGT process is really able to change this situation or it is simply going to legalize it further.

In order to better understand the situation, we start by briefly outlining the historical roots of the marginalization of forest communities. We then provide a discussion of power issues within the forest sector as well as an inventory of its impacts on local populations. After a brief analysis of the shortcomings of the measures that have been taken, especially the 1994 forest law, we focus on the most recent one – the new FLEGT process – before ending with some concluding remarks and recommendations.

Map 1. Vegetation in Cameroon. (Source: Ministry of Forestry and Wildlife and World Resources Institute, Interactive Forestry Atlas of Cameroon, version 2, Yaounde, 2007)

.

2.1 Power imbalance in extractive processes

2.1.1 The colonial legacy

According to customary institutions, local communities – whether Bantu or “Pygmy” – have ownership rights over the land and the natural resources on which they depend for their daily survival. These ancestral customs have been under threat since the beginning of the colonial period, when, in 1896, the German administration introduced written norms using the questionable concept of “vacant and ownerless lands”. In this way, the colonial state was able to appropriate all land and resources through the transformation of common pool resources into state and private property. This process happened through a double movement: (1) the creation of rights for new actors: the colonial state and for private persons (physical or moral); and (2) the considerable restriction of the populations’ access rights to land and resources.

In fact, a given plot of customary land could only be claimed as property when its owner was able to prove its mise en valeur (economic profitability) through cultivated fields or constructions. However, as many anthropological studies have revealed, the customary land of Bantu forest societies goes beyond the cultivated or inhabited areas and encompasses large portions of forest that are collectively managed (Diaw, 1997; 1998; Oyono, 2002; Bigombé Logo, 2004). The problem was still more difficult for the indigenous “Pygmy” communities whose hunter-gatherer lifestyle has little impact on the forest cover and their presence on a given area was therefore difficult to establish (Abega, 1998). The large areas they covered in search of food and other resources were consequently declared vacant by the colonial administrations and taken under its control – a practice that would be reinforced after independence (Nguiffo et al., 2008).

From 1960 onwards, independence was not at all characterised by a rupture in the philosophy of colonial law. This can be explained by the fact that the genuine independence movement was largely suppressed by the French army. Between 100,000 and 400,000 civilians sympathetic to the UPC (the “Union des Populations du Cameroun – the main nationalist movement) were killed and their socialist leader Ruben Um Nyobé was assassinated by the French in 1958 (Survie, 2006). The only two Cameroonian presidents since then have behaved as “straw men” of France, to take up the expression of the famous Cameroonian writer Mongo Beti. The secret – and sometimes bloody – political-economic connections that continue today between France and Africa have been referred to as the “Françafrique”, and have been traced to 1960 under De Gaulle. The term was coined in 1994 by French journalist François-Xavier Verschave who was a specialist on the phenomenon. These kinds of geopolitical relations are of importance for understanding institutional and economic change in French-speaking Africa but they are rarely mentioned by researchers (Agir Ici and Survie 2000; Survie 2006).

Despite the resistance against the first post-colonial legislations, Cameroon’s “land tenure nationalism” (Diaw, 2005) culminated with the 1974 law, still the basis of today’s land regime. The colonial notion of “vacant and ownerless land” was taken up again to the benefit of the state and ambiguously recognized a limited space for customary institutions. In this process, forests were a major target, as securing bureaucratic control over forested land and timber constituted a critical ingredient in the mix of political-economic forces which historically shaped territorial nation-states across the globe (Neumann, 1997).

.

2.1.2 Today’s macroeconomic actors in forest management

It can be argued that Cameroon – along with other countries in Equatorial Africa – is still subject to a system of neo-colonialism, perpetuated by the former colonial powers, by foreign capital and by the ruling classes at the national level. Germany, France and the United Kingdom all played a significant part in the colonial history of the country and remain influential “partners” on trade and macroeconomic policies. They are joined in their enterprise by other Northern governments, as well as by multilateral agencies, notably the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) – in which they occupy strategic positions. For the most part, the former colonial countries and their home-based transnational corporations remain in a key position for dictating the terms of development and conservation in the region.

Foreign creditors and donors have always been very active in the forest sector and their assistance programs are generally conceived with the (naïve) intention of promoting both economic growth as well as ecological and social sustainability of forest activities. Despite numerous improvements in forest sector brought by the reform process that started at the end of the 1980s, the impact of their “goodwill” has, however, been limited. For instance, the World Bank and the IMF have persisted in supporting the development of the logging industry on the pretext of increasing state incomes but remaining apparently blind to the weakness of the same state – Cameroon was rated by Transparency International as “perceived to be the most corrupt country” in its international survey of 1998 and 1999.

Since independence, the State’s main aim in the line of development policies has been to foster the industrial extraction of timber. Official discourse stresses the important contribution of the timber industry to national economic growth. Indeed, the state is a strategic actor in the management of Cameroonian forests, as it owns the forest and defines forestry policies and regulations. However, at the same time, it has an ambiguous power position for three main reasons. Firstly, as the government wants to attract direct foreign investments, it hesitates to be strict when companies commit even the most serious offences. Secondly, its capacity to monitor and enforce legislation is in any case minimal and limited both by corruption and structural adjustment policies, which have reduced the number of civil servants and their salaries. Thirdly, there is often a mutually beneficial relationship between political elites and foreign economic operators, involving the appropriation of wealth for both parties through bribery, corruption and transfer pricing at the expense of public benefit through lost revenues and royalty payments as well as at the expense of forest-dependent communities.

The economic operators involved in timber production are obviously key stakeholders in Cameroon’s forest sector. Their objective is to maximize their financial benefits, which is easy to achieve in a corrupt country such as Cameroon. Since the colonization until now, almost all timber extracted in Cameroon is exported to Europe and, since 2005, also to Asia. French entrepreneurs launched the three first important companies in Cameroon in 1949 and French companies continue to be key operators in Cameroon – in logging activities as well as in plantations (Etoga Eily, 1971; Obam, 1992). The logging and timber processing industry is highly concentrated, with more than 80% of national timber extraction being generated by fewer than 20 large, predominantly European, companies (Cerutti and Fomété, 2007). Recently, Chinese operators have established themselves, either through the acquisition of European interests, or through acting as contractors for national interests (Karsenty and Debroux, 1997).

.

2.1.3 Accumulation by dispossession

The transition to capitalism has often been preceded by land appropriation by large private landowners and/or by the state, through different kinds of “enclosure movements”, physical as well as legal. The English version of this process was defined by Polanyi (1944) as a “revolution of the rich”. In Cameroon, Western law allowed the colonial administration to secure its access to natural resources by transforming customary common pool resources into state property. This phenomenon has led to an unequal repartition of property rights allowing capitalist accumulation through the dispossession of local communities (Harvey, 2003). A Western-type property regime is indeed central in the functioning of capitalism itself by standardizing the economic system, by fixing the economic potential of resources in order to allow credit and selling contracts, and by protecting (by armed force if needed) property and transactions (Heinsohn and Steiger, 2003).

Today, the approach of standard economics still emphasizes the necessity to extend a Western-type property system to all kind of goods and services in order to ensure growth and even “sustainability”. Surprisingly, such policies still frequently refer to Hardin’s (1968) “tragedy of the commons”, which confuses regimes of open access with those of common property. According to Hardin, private/state property would supposedly allow the conservation of natural resources due to the clear definition of rights and duties. However, this theory has been criticized (Ostrom, 1990). The important point is to achieve a correct match between institutions, and the cultural and biophysical environments. Indeed, anthropological studies have shown that societies have often developed institutions regulating access rights to natural resources and duties between the different community members in order to ensure the social functioning of the group and the management of natural resources (Berkes, 1999). Thus, the transformation of common pool resources into state and private property – such as in Cameroon – has often been socially unequal and ecologically unsustainable.

Ecological historian Alf Hornborg (1998: 133) has defined three factors entering into any process of industrial accumulation: (1) the social institutions which regulate exchange; (2) the direction of net flows of energy and materials; and (3) the symbolic systems which ultimately define exchange values and exchange rates. So far, we have discussed the first two factors: first, how a Western-style property regime has become the official set of institutions legitimating and providing the colonial state – and then the independent state – the legal capacity to make claims over other people’s resources; and secondly, how today’s control over the flows of timber is carried out by a limited number of economic actors. Later, we shall tackle inter alia the symbolic system – the dominant “language of valuation” – that imposes unjust monetary exchange values to the detriment of other value systems.

.

2.2.1 Impacts on local populations

Logging companies consider the forest only in its economic dimension and their single objective is to maximize financial benefit. Their “grab-it-and-run” logic – a good example of what early 20th-century European geographers called Raubwirtschaft – consists in extracting the maximum of rich timber species in very little time, without concern for sustainability. These practices are based on high discount rates, indicating an undervaluation of the future. Companies want to get profits to pay back debt to banks (that charge interest rates), to pay dividends to shareholders, and to make further investments. Profits are obtained by discounting future sustainability. Accordingly, companies perceive sustainable management as a constraint to overcome. The impacts of this extractive model will be discussed next.

Although selective logging causes less damage to the canopy than clear cut logging, it provokes direct and indirect negative environmental effects. In particular, the search for the best trees means that companies build roads into relatively large areas of forest to extract the few wanted trees. This practice destroys the peasants’ fields and opens up the forest to human settlements, to the development of agriculture, and to commercial hunting. While bush meat is traditionally important for forest peoples, the development of large-scale commercial trade in bush meat is relatively recent and has been directly and indirectly facilitated by the development of timber industries. As a result, wildlife populations are being decimated, including rare and endangered animals such as elephants (Loxodonta africana cyclotis) and lowland gorillas (Gorilla gorilla).

Although promoters of timber exploitation argue that selective logging on large concessions is required in order to reach sustainable management, none of this, in actual practice, is proven to be true (see Debroux, 1998). Present logging methods are very destructive since the extraction of each cubic meter of wood implies the destruction of larger volumes, resulting in a significant change of the initial ecosystem diversity. Harvested volumes can be as low as 5–6 m3/ha out of a potential volume of 35 m3/ha. This is because only a few high value timber species (8% of known species) are extracted from the forest for commercial purposes. Among these species, six represent almost 80% of Cameroon’s timber production: Ayous (Triplochition scleroxylon), Sapelli (Entandrophragma cylindricum), Azobe (Lophira alata), Frake (Terminalia superba), Tali (Erythrophleum ivorense) and Iroko (Chlorophora excelsa) (Auzel et al., 2003). Other high value species which are harvested include Moabi (Baillonella toxisperma), sacrificing their use by the local communities to extract oil, fruits, and for medical purposes (Betti, 1996), and Bubinga (Guibourtia sp.), which has spiritual and medicinal values as well. In addition, it is important to note that there is much waste of the valuable wood – up to 25% of raw logs – at the logging sites in the forest as well as at the sawmill (Gartlan, 1992).

.

2.2.1.1 Further limitations of conventional approaches

Conventional economists and policymakers usually look to a country’s GDP when measuring its “economic health”. However, GDP measures only the monetary value of goods and services produced and does not account for the physical flows of materials and energy within the economy which says a lot about the environmental impacts. Indian ecological economist Pavan Sukhdev found that the most significant direct beneficiaries of forest biodiversity and ecosystem services are the poor, and the predominant impact of a loss of these inputs is on the well-being of the poor. The poverty of the beneficiaries makes these losses more acute as a proportion of their “livelihood incomes” than is the case for the people of India at large, hence the notion of the “GDP of the Poor”.

Instead of focusing on monetary cost/benefit analyses, ecological economics argues for evaluating any given economic activities through their biophysical dimensions as a way of highlighting their (un)sustainability. This is for instance investigated through material flow analyses (MFA) that looks at what materials are extracted, imported and used in a given region or in a given economic sector and with what consequences. An MFA of industrial logging in Southern Cameroon would be interesting from an activist perspective because it would assess its unsustainability. In effect, it could be potentially quite subversive to look at:

• How much energy – oil – is needed for the typical process of timber extraction and for its exportation? (i.e. oil for the chain saw, the truck, the sawmill, the boat). The whole extraction/export process would appear as a pure madness from an energy point of view when compared, for instance, to the consumption of local populations.

• How much biomass (i.e. forest plants) is destroyed by extractive machines and roads in order to reach the wanted species? In other more technical words, what are the “hidden flows” or “rucksacks” of selective timber extraction (meaning the “extra-economic”, “forgotten” damages of timber extraction)? This figure is probably quite impressive, in tons. Again, the whole extraction process would appear as deeply unwise in view of the amounts of wastes and damages caused (in terms of biomass destruction).

• How important is timber, from a physical perspective, for the importing economies? Cameroonian timber is not an essential bulk commodity for the metabolism of the importing countries. It is different from imports of oil, gas, phosphates, iron ore or steel, wood and wood products for paper. It would be insignificant in tonnage. It would clearly appear as a luxury good for some sectors of the upper classes, thereby emphasizing its futility and the recklessness of timber extractors as well as European consumers (when compared to local impacts). The European consumers suffer from something that in the CEECEC project we have come to call “consumer blindness”, a social ailment that the activists of fair trade would like to cure.

• How important are wastes? Also, within the sawmill the quantity of material wasted would be accounted for in a MFA analysis.

Part of the rationale for promoting industrial timber production is that the sector contributes to poverty alleviation. This “underlying principle” needs to be challenged. A 1991 Oxfam report concluded that opening up Africa’s forests to exploitation would “cause an increase in poverty rather than its resolution” and a 1990 report for the European Community stated that “forestry development and deforestation generally go hand in hand with the redistribution of wealth from the poorest (…) to a national elite and foreign companies (and) widens the gap between the rich and the poor in tropical countries” (Witte, 1992). For instance, contrary to what promoters say, the direct benefits of logging in terms of infrastructure development (schools, clinics, churches, etc.) are poor. Evidence shows a complex and far from positive picture of the impact of such operations.

Some employment opportunities arise, but not necessarily for people living locally. The best jobs in the foreign companies are for foreigners. Jobs in the logging industry are often short-term and remuneration can be very low. Facilities for the workforce are sometimes provided but their conditions are often poor and restrictive. Diseases such as alcoholism, malaria, ulcers and tuberculosis are widespread in the workers’ camps. Forestry operations act as a magnet, often attracting thousands of newcomers deep into the rainforest. These new settlements are totally dependent on forestry activities. Once the timber extraction finishes, the towns invariably collapse. Such boom-and-bust townships are not sustainable: they cause social tensions between newcomers and existing communities, increase pressure on natural resources including bush meat, and facilitate alcoholism, prostitution and illnesses.

In many cases, the degradation of forests implies a disruption of successful local economies. Traditional ways of life are being eroded, threatening food security and livelihoods. Non-timber forest products (NTFP) become scarce, resulting in a direct loss of income for many forest-dependent populations. Women and the elderly are particularly badly affected as they are often the ones to collect and trade NTFPs, providing valuable food and cash for their families. Timber trees such as Moabi and Sapelli, for instance, have been highly valued for their many uses. Their over-exploitation has seriously disrupted local livelihoods and has led to a net loss of cash income for many.

In addition, beyond Cameroon itself, there is a loss of the environmental services provided by forests. Forests are sinks for carbon dioxide, the main gas causing an increase in the greenhouse effect.

.

2.2.2 Conflicting languages of valuation

The forest is thus a site of conflicts between competing values and interests represented by different classes and groups. How are such conflicts to be understood? The approach of standard economics (even when labelled “environmental”) is to use of a common unit – a monetary numeraire – for all the different values and then to look for a compromise (a trade-off) between all of them within a market context. By “values” we understand what is considered important: conservation of nature? sacredness? livelihood? aesthetics? money? national sovereignty? Typically, conventional economists apply monetary compensation to the injured party to solve conflicting claims, using for example cost benefit analysis and contingent valuation methods. In some cases, as when asking for redress in a court of law in a civil suit, this is what is done: asking for money as compensation for damages. This approach assumes therefore the existence of value commensurability, that is, all values can be translated into money.

Ecological economists, in contrast, accept value incommensurability (Martínez-Alier et al., 1998). If a territory is sacred, what is its value in money terms? If the livelihood of poor people is destroyed, can money really compensate for it? Nobody knows indeed how to convincingly estimate the monetary price of cultural, social or ecological impacts of, for instance, deforestation. Instead of appealing to a unique numeraire, other ways are available for resolving problems related to a plurality of values.

In Southern Cameroon, the languages of valuation used by local populations are diverse. Most of the time, it is not the language of Western conservation (e.g. “biodiversity protection”) nor it is the one of standard economics (e.g. “monetary compensation”): local populations use the languages of defence of human rights, urgency of livelihood, defence of cultural identity and territorial rights, respect for sacredness. The following information is relevant. Because of logging, “Pygmy” Baka lose bush meat, territory, trees, and product collection spots. However, they often say that the main prejudice they suffer from is noise pollution from chainsaws and trucks. In the Baka cosmology, when God created the world (humans and Nature), his favourite activity was to listen to the bees. So, humans had to stay quiet in order not to disturb God. But one day, some Baka began to make noise in the forest and God punished them by transforming them into wild animals. Noise is thus considered by Baka as a severe impact of logging since it is directly related to their religion, creating a “spiritual prejudice”.

In view of this, it is misleading – as standard economists do – to try to reduce such a diversity of languages to a single monetary measure and to put a price on forest degradation. Conventional conflict resolution through cost/benefit analysis and monetary compensation is therefore inappropriate because it denies the legitimacy of other languages. It simplifies complex value systems related to the environment into monetary units. Moreover, if the only relevant value becomes money, then poor people are disadvantaged as their own livelihood is cheaply valued in the market. The compensation will be scarce. Therefore, market prices and monetary valuation are themselves tools of power through which some sectors impose their own symbolic system of environmental valuation upon others, thereby defining exchange values and allowing the trade-off of economic benefits and socio-environmental costs in their own favour. In fact, we realize that poor people are well advised to defend their interests in languages different from that of monetary compensation for damages, because in the capitalist sphere the principle that “the poor sell cheap” is operative (Hornborg et al., 2007).

Values are often incommensurable. This means that they cannot be measured in the same units. It then appears that only a truly democratic debate can solve valuation contests. Social multi-criteria evaluation is a tool from ecological economics that allows the comparability of plural values and sometimes helps to reach compromise solutions. It also shows which coalitions of actors are likely to be formed around different alternatives (Munda, 1995). In reality, however, it is usually the most powerful actor that imposes his own viewpoint and language of valuation. In this context, quite obviously, conflicts are sometimes the only way to change power relations favouring the dominant actors, and to advance towards equity and sustainability.

.

2.2.3 Unequal patterns of trade

The present structure of trade relations between different world regions is, to a large extent, a consequence of the international division of labour, which has developed since the beginning of colonization in the 16th century (Wallerstein, 1974; 1989). This process has structured Southern economies according to the interests of industrialized countries, transforming them into suppliers of bulk raw materials, precious commodities, and cheap labour in logging, plantations, mines, and ranches.

These imposed directions of material flows inevitably lead to an unequal distribution of environmental burdens related to extraction activities, i.e. to an ecologically unequal exchange, where negative environmental impacts are shifted to poor world regions and “clean” final products are exported to rich countries (Bunker, 1985; Altvater, 1994; Hornborg, 1998; Muradian and Martinez-Alier, 2001). International trade opens the possibility for industrialized countries to maintain – or even increase – the national environmental quality without changes in the resource intensity of the population’s increasing consumption. This is possible because world markets prices of raw materials or other exported goods do not take into account their depletion as well as local externalities (Cabeza-Gutés and Martinez-Alier, 2001; Hornborg et al., 2007). In this way, the negative environmental impacts are shifted to the extractive periphery while wealth is accumulated in the centres. The notion of an ecologically unequal exchange highlights the fact that the specialisation of Southern countries in primary exports tends to impoverish the environment upon which local populations depend for their livelihood. This applies also to regions within large countries (eg. Brazil and India).

Considering the limited power of Southern countries on world markets and the falling prices for primary commodities (as we see now again in the crisis of 2008–2009), revenues and debt service payments can often be maintained only through an increase of physical export volumes. According to Giljum and Eisenmenger (2004), these mechanisms allow “the maintenance of high levels of resource consumption in the North and lead to environmental destruction and the maintenance of unsustainable exploitation patterns in the South”. The ecologically unequal exchange highlights power imbalance. The logging of Cameroonian forests is a prime example of this phenomenon.

Conventional economics looks at environmental impacts in term of externalities which should be internalized into the price system. One can see externalities not as market failure but as cost shifting success, however which can sometimes backfire for business companies because they might give rise to environmental movements (Martínez-Alier (2002: 257). One conclusion is that “the focus should not be on ‘environmental conflict resolution’ but rather (within Gandhian limits) on conflict exacerbation in order to advance towards an ecological economy” (ibid.).

During the early 1990s, the idea of the North’s ecological debt to the South began gaining currency (especially in Latin America). Friends of the Earth International – to which the CED also belongs – gave support to this notion in some of their meetings and writings. Activists have been at the forefront of this discussion. Ecologically unequal exchange and the disproportionate use of natural resources and environmental space by industrialized countries are the main reasons for the claim of the ecological debt. Examples of unpaid costs that the North owes to the South with respect to industrial logging are inter alia: (1) unpaid costs of sustainable management of renewable resources – especially the trees that have been extracted/exported; (2) the costs of the future lack of availability of destroyed natural resources; and (3) the compensation or reparation for local damages produced by exports (such as the destruction of forests, fields or graves). Of course, these aspects of the ecological debt defy easy measurement. However, although it is obviously not possible to make an exact monetary valuation, it is certainly useful to establish the orders of magnitude in order to stimulate political debates and consciousness-raising. The social and ecological consequences of logging activities will be developed in the next section.

The moabi tree (Baillonella toxisperma) provides a good illustration of ecologically unequal exchange giving rise to environmental conflicts expressed in different languages of valuation. Various interests and cultural values crystallize around this species: this moabi is (1) endemic to the Congo basin forest and endangered, (2) particularly valued by loggers, as well as (3) essential for local populations and especially for women.

• It is Africa’s largest tree – some specimens can reach 70 meters of height, five meters in diameter and up to 2,000 years of age – and it is emblematic of the ecological damage caused by commercial logging. Its biological characteristics make it very sensitive to industrial exploitation because its reproduction is fragile due to a slow growth rate, a late sexual maturity (after about 70 years), a spaced fructification periodicity of about three years, and a high predation rate on seeds and young stems (Debroux, 1998). Moabi are today rare in the littoral region, where commercial logging started about one century ago, while it is still possible to find them in the south-eastern region of the country. The Canadian International Development Agency has classified it as an “endangered species” and Friends of the Earth International campaigns for its inclusion in the Red List of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES).

• The moabi is the eighth most exported tree species in Cameroon (in volume of sawn logs), a fact that shows how sought after this species is by commercial loggers. Its price per cubic metre is very high, making of it more of a “preciosity” than a bulk commodity. It is a luxury consumption good, used for furniture, parquet, yachts and so on. The six main groups of moabi loggers own 40% of the forests affected by logging. In 2005, they produced 92% of the moabi national production. The French groups (Pallisco, Rougier) have produced 45.2% of the total moabi production from 2000 to 2005 and the Italian groups (Patrice Bois, Fipcam) 19.6%. Like all Cameroonian timber, moabi are integrally exported to industrialized countries. France has imported 71% of the production from 2000 to 2005 and Belgium 23.5%. Accordingly, moabi trade takes place in the continuity of the commercial relations that began under the colonization.

• In parallel, the moabi is a central element of forest societies of Southern Cameroon who complain and resist its logging. The moabi fulfils four central functions: cultural, medicinal, food and, now, economic. First, deceased important persons were traditionally sat at the bottom of the tree or in a cavity of the trunk and left there to decompose; the moabi became thereafter a totem embodying the power of the ancestor. Second, more than fifty medicines can be prepared using moabi leaves, roots, sap or bark, such as those to cure vaginal infections and for healthcare related to childbirth. Third and fourth, fruits are consumed and the seeds produce oil used for self-consumption as well as for sale on a limited scale. The production of oil is controlled by women, from the collection to the commercialisation.

In the conflicts over the moabi, this tree is accordingly not only valued through the language of standard economics (that is, market prices). While forest societies refer mainly to the defence of livelihood (including health, food and income), cultural values (including sacredness and the defence of customary rights) and social justice (illegitimacy of logging practices), the logging companies typically use the idioms of economic growth and state law. Such conflict can be understood as a clash on valuation standards. The concept of an ecologically unequal exchange is also relevant as the price of the moabi timber does not take into account its depletion nor local externalities. Indeed, the majority of the benefits remain in Western countries – and particularly in France – while most environmental and social costs are imposed on the country and particularly on the populations of the extractive regions.

.

3.1 The 1994 Law

3.1.1 Involvement modalities of local communities

In order to solve the growing conflicts related to industrial logging, in 1994 the state adopted a new set of forestry laws that came into force under the auspices of international actors such as the World Bank (Bigombe Logo, 2004; Cerutti and Tacconi, 2008; Ekoko, 2000). A zoning plan was designed that divides the forest territory into a Non-Permanent Forest Domain (NPFD) and a Permanent Forest Domain (PFD), itself divided into about 100 Forest Management Units (FMU) from which the majority of the bulk of annual timber harvest is collected. Among the main changes, there is a declared will to associate communities to forest management and to the benefits generated by logging, through the creation of (1) “legal” community forest and (2) annual forestry fees.

Such “community forests” remain within the NPFD and correspond to a maximum area of 5,000 hectares, whose management is attributed by the state to given communities for a period of 25 years renewable. Local populations thought that the creation of “official” community forests would be a way of claiming their customary institutions and secure a peripheral area around their villages. However, in reality, the formalization process is a huge challenge for them as it is complicated, time-consuming, onerous, and the administration’s free support mentioned by the 1994 law was never turned into practice (Nguiffo, 1998). Moreover, the treatment of community forest by the administration is more severe than that of industrial logging concessions with respect to forest management plans and sanctions. [A management plan is required before any exploitation for community forest, while for logging concessions, a provisional agreement of three years allowing exploitation is conceded. In case of law offences, there is direct cancelling of the community forest permit against a gradual system planning financial sanctions for logging companies.] Finally, the areas allocated for community forests are virtually always much more limited than the customary ones. These points highlight the fact that the zoning plan was designed without taking into account the customary institutions and forest management of local populations.

A new taxation system was also put in place as part of the legal requirement for exploiting state concessions: 10% of the new annual forestry fees are allocated to local communities, 40% to city councils, and 50% to the state. The 40% to councils is also supposed to be used for the development of communities. Although it is a good idea to tax natural resources that are exported (sometimes this is called “natural capital depletion taxes”), in reality these taxes are often misappropriated by local bureaucracies and rarely get down to the people.

Thus, despite of the social benefits of the 1994 law, in practice, populations experienced huge difficulties to accede to what they in principle had rights to. In February 2000, a workshop organized by the British government found that industrial timber production in Cameroon “tends to benefit a small minority (often foreign investors), and its contribution to poverty alleviation is minimal” (Hakizumanwani and Milol, 2000). The workshop made a series of recommendations which would need to be implemented before local development could be equitably achieved, including (a) greater transparency in the use of the income generated by forest resources; (b) equity in the redistribution of income as local communities see just a tiny fraction, if any, of the money generated by logging; (c) institutional decentralization; and (d) the creation of favourable conditions for local people to climb out of poverty through self-initiative.

.

3.1.2 Achieving sustainability: the illegality trap

Another objective of the 1994 forest law was to promote the sustainable exploitation of the forest through the creation and reinforcement of protected zones, through the implementation of a minimum standard in terms of forestry management practices, and through the eradication of illegality. It has fostered a revival of Cameroon’s interest in conservation.

The 1990s saw the beginning of many projects related to protected areas in the South of Cameroon: Korup, Mount Cameroun, Dja, Campo-Ma’an, Lobeke Lake, Boumba Bek and Nki. The scarcity of the state’s means and the low technicality of its personnel have attracted foreign aid agencies involved in the management of such areas: in all cases, their management is supervised by international conservation NGOs, particularly by the WWF. The problem with such projects is that the regime on protected areas imposes important restrictions on local communities regarding their access to land and forest resources. Indeed, the law often proscribes any human activity in protected areas. In this field also, the objectives of involving local communities with the management of protected areas are not being translated into facts, instead, transforming the protected areas into a field of fierce confrontation between local communities and conservation agencies or state administrations, sometimes culminating into exchanges of insults or shots (Nguiffo, 1998).

With respect to management practices, the FMU system has replaced the former system of concessions. FMU are allocated by auction to a company for 15 years renewable and force loggers to set up a management plan, respecting minimum standards of exploitation that has to be approved by the administration. However, reaching that minimum seems to be the exception rather than the rule. Forestry officials do not have the capacity to monitor the operations of companies nor to enforce legislation.

In that context, illegal logging and trade in timber has, since the beginning of the 1990s, continued to increase and today has reached worrying proportions. The 1994 forest law was the first attempt in reaching sustainability and equity, assuming that a “good” legal system would constitute per se an adequate and sufficient response. Later on, in view of the systematic violation of the law – including by those who were supposedly in charge of enforcing it – several “independent observers” were created and contracted, such as Global Witness, Resource Extraction Monitoring, Global Forest Watch, and Cameroonian private firms. They are mainly active at two stages: (1) in the commission allotting FMU and (2) in the legal monitoring of forestry operations. However, independent observation has quickly shown its limits: if it is true that these observers improved the understanding and exposure of illegal activities (tax evasion, timber quantities), they never had the power to guarantee sanctions. Indeed, very few companies have been sanctioned on the basis of the reports of independent observers.

.

It is important to understand that logging companies are not the only actors involved in illegal practices. The administration also plays a key role – and this is why mitigation policies (such as the FLEGT process that will be discussed below) are likely to be ineffective. The state benefits from a presumption of legality. However, since the first years following the implementation of the 1994 law, it was not unusual that decisions taken by the administration were in flagrant violation of the legislative and regulative clauses in force. Several strategies aiming at circumventing the law have been used. The following can be mentioned:

• Allocation of concessions outside the legal process. It is through Decree no. 96/076 of 1 March 1996, signed by the Prime Minister, that the government has allotted the first concessions, following the 1994 reform. It concerns five Forest Management Units (FMU) that were allocated exceptionally and in complete illegality to the companies Coron and CFC (Compagnie Forestière du Cameroun). The five FMU represent a total area of 334 158 hectares. The allocation resulted from a procedure based on mutual agreement against the law. Moreover, although the law imposes a maximal area of 200 000 hectares for such FMU, the CFC apparently received 215 680 hectares (Durrieu de Madron & Ngaha, 2000), instead of the 197 398 hectares announced in the notification letter prepared by the MINEF. [See Correspondence No. 045/L/Minef/DF/SDEIF of 13 August 1996 to the Management of the CFC.] This inaugural allocation clearly indicated a line based on opacity, in spite of the clauses of the new law and the proclaimed objectives of the forestry reform in favour of more transparency.

• Allocations of concessions in violation of the results of the auction system. In accordance with the 1994 law, the MINEF has published in January 1997 the very first invitation to tender for the granting of forestry concessions in Cameroon. [See Auction No. 0158/AAO/Minef/DF/SDIAF of 13 January 1997.] It concerned 23 FMU, representing a total of 1 685 000 hectares. In October 1997, the beneficiaries of the new FMU were notified, through the Forest Department, about the results of the deliberation of the Commission allocating concessions. After a closer look at the results, it became obvious that the final beneficiaries had not always been the highest financial and technical bidders. In one third of the cases, the final beneficiaries had not been recommended by the Commission and among the 15 companies chosen by the Commission only five were the highest bidders with the best technical scores. Objectivity is therefore far from having ruled the first invitations to tender in Cameroon. And the World Bank admitted in a 1998 report: “Finally the Government has started to auction cutting rights, but […] in the October 1997 allocation of concessions, the specified allocation criteria have not been fully respected. Bidders are supposed to be preselected based on minimum technical qualifications, and the highest prequalified bidder. But concessions were awarded to the highest bidder in only 10 of 25 cases. In most of the cases (16 of 25), concessions were awarded to the most technically qualified bidder. In other cases, concessions were awarded to bidders with low technical ranking and low bids” (World Bank, 1998: 17). These opaque processes have had a significant cost for state finances: because of the non-allocation to the highest bidder of some of the FMU, it is estimated that the state loses about 4 million euros per year (GFW, 2000).

• De facto extensions of the duration of provisional conventions. The 1994 law stipulates that beneficiaries of concession titles can only enjoy a provisory convention of a maximum length of three years, “during which the industrialist is obliged to complete a certain number of works, notably the installation of industrial unit(s) for wood transformation”. [See Article 50(2) of the 1994 forestry law.]Article 67(2) of the Decree of 23 August 1995, providing for the application modalities of the forest regime, specifies the nature of the works in question: an inventory of the management, the elaboration of a five-year management plan, an operation plan for the first year, the delimitation of the exploited areas, and the installation of a transformation unit. These works are executed under the responsibility of the logging company. Many provisional conventions have lasted for more than the three years provided for by the law and without carrying out the realization of these works. Although such breaches are sometimes the administration’s fault (but not always), it remains nevertheless true that they are violations of the law – and violations that the FLEGT process will have to deal with. Technically, the timber taken out from these concessions is illegal as the law does not provide for an extension of the provisional convention.

• Delocalisation of ventes de coupe. Ventes de coupe (cutting permits) are part of the forestry devices provided for by the 1994 law. They consist of authorisations to exploit during a limited period of time a precise volume of wood on an area no larger than 2 500 hectares. If a vente de coupe is planned on a given forest zone, the project must first be presented to the neighbouring communities, who benefit from a preferential right if they want to ask for a community forest on the same area. If local communities have no interest in it, the MINFOF starts a public auction process for the vente de coupe in question. Following this, bidders are invited to visit the site in order to better prepare their offer. When offers have been sent to the MINFOF, they are opened by an Interdepartmental Commission allocating titles composed inter alia of an Independent Observer. At the end of the process, the best offer is chosen and the MINFOF signs an allocation decree of the vente de coupe. However, these requirements are not always respected by the administration and it is not rare that such ventes de coupe are allocated at places different than those indicated in the invitations to tender. This was for instance the case for 15 ventes de coupe that were visited by the Independent Observer in October 2007. [See Quarterly Report No. 10 of 6 October 2007 (www.observation.cameroun.info.org).] Called out by the latter, the Forest Department confirmed that the ventes de coupe concerned had been displaced and intended to justify such illegality by explaining that the beneficiaries, once they had already paid all the legal fees, discovered that the titles were localised on places without forest cover, notably on markets, schools and villages.

• Abusive use of authorisations for recuperating wood. Such authorizations are generally given when roads, plantations or any development project are planned. These last few years, they were at the heart of serious governance problems within the MINFOF. [See Annual Report of March 2007–March 2008 of the Independent Observer (www.observation. cameroun.info.org).] These titles – formerly considered “small” in view of their maximal area of 1 000 hectares, their limited validity periods, and their limited quantities of timber produced – became the second source of wood supply after the FMU because of systematic abuses. During 2006, they concerned an annual volume of more than 300 000 m3 of wood. Following a series of missions, the Independent Observer reported that more than 80 per cent of them resulted from illegal procedures. [See Annual Report of March 2007–March 2008 of the Independent Observer (www.observation. cameroun.info.org).] The most common cases are title delocalization, beyond-limit exploitation, fraudulent use of marks, and non-payments of taxes. According to the same report, a large part of these illegalities are endogenous to the MINFOF. The trafficking of waybills (lettres de voiture) around areas of authorisations for recuperating wood also apparently originates from the MINFOF itself, as well as the erroneous and partial entries in the computer-aided management system of forestry information (SIGIF), making this tool malfunctioning and useless. It turned out for instance that because the Direction of Forests did not reclaim and follow up the effective use of the waybills, many of them remain in the hands of loggers and are subsequently used in the laundering of illegal timber.

The problem of illegal logging and the trade in associated timber products led the European Union (EU) to propose a new type of legal device that will be analysed next: the Forest Law Enforcement, Government and Trade (FLEGT) process.

.

3.2.1 Origin and scope

FLEGT traces its roots as far back as 1998. It arose from the recognition that illegal logging results in serious environmental and social damage, as well as severe loss of income to governments. In a G8 Summit in 1998, where measures to tackle illegal logging were discussed and an “Action Programme on Forests” formally adopted, it was acknowledged that illegal logging costs governments an estimated $10 billion every year in lost revenues. In 2002 at the World Summit on Sustainable Development held in Johannesburg, the European Commission set out a strong commitment to combat illegal logging and the associated trade in illegally-harvested timber. The EU published its first Proposal for a FLEGT Action Plan in May 2003. A number of other initiatives, arising from both national and international commitments, have developed in parallel. In particular, three regional FLEG (Forest Law Enforcement and Governance) processes have been established in South East Asia, Africa (AFLEG) and Europe and North Asia (ENAFLEG). These processes, co-ordinated by the World Bank, have resulted in ministerial commitments to identify and implement actions to combat illegal logging in each region.

The main objective of FLEGT is to combat illegal logging and the trade in associated timber products. This must be seen as part of an EU policy to secure imports of natural resources in a manner that causes less conflict. The EU is a very large net importer of natural resources. To achieve this aim, one of the strategies used is to provide support to timber-producing countries. This is done through the conclusion of Voluntary Partnership Agreements (VPA) with timber-producing countries that wish to eliminate illegal timber from their trade with the EU. These agreements will involve establishment of a licensing scheme to ensure that only legal timber from producing countries (so-called “Partner Countries”) is allowed into the EU. Unlicensed consignments from Partner Countries would be denied access to the European market under the scheme. The agreements are voluntary, meaning that Partner Countries can decide whether or not to sign up, although once they do so the licensing scheme is obligatory.

Currently there is no law to prevent illegally-logged wood products from being imported into the EU. A new EU regulation is therefore required to empower Member States’ customs authorities to enforce this scheme. Proposals for a regulation and a mandate that would authorise the European Commission to negotiate agreements with potential partner countries are currently being finalised. Cameroon should sign a VPA by the end of 2009. Each VPA will require a definition of “legally-produced timber” and the means to verify that wood products destined for the EU have been produced in line with the requirements of this definition. Both the definition of legality and the verification system should be appropriate to circumstances in the Partner Country. Details of these will be negotiated between each Partner Country and the EU. Where needed, EU development assistance will be provided to help establish licensing schemes.

.

3.2.2 Critical analysis of the FLEGT-Cameroon

3.2.2.1 Stakes of the FLEGT process

An appropriate application of a VPA in Cameroon seems very delicate as the parties involved have various expectations and interests (avowed or not) with respect to the FLEGT:

• The main aim of the EU is to ensure that all wood and derived products that enter its territory come from legally logged and exported trees, on the basis of the national definition of legality of the producing country, integrating at best all aspects of sustainable forest management.

• Cameroon’s government seems to perceive the FLEGT, on one hand, as an instrument able to promote and enforce the technical and fiscal aspects of forest management and, on the other hand, as a marketing tool able to promote and show a political will of forest “good governance” allowing to seduce donor partners and to attract foreign capital.

• The main goal of the private sector seems to be to make sure that the standards developed within the FLEGT process will be less restrictive and as credible as the ones prevailing in certification schemes such as the Foresty Stewardship Council (FSC). However, there might be private sector actors who see in FLEGT a chance to differentiate their “high quality” product and achieve higher prices.

• Civil society expects that the FLEGT process will integrate into the definition of legality the principles and criteria related to ecological, social and economic sustainability (such as the ones used in the certification) as well as participation (such as the rights of indigenous people). Civil society hopes thus that the process will lead to a compulsory standard of legality including sustainability and the recognition of human rights, including indigenous territorial rights.

.

3.2.2.2 Definition of legality

A questionable consensus was reached by the members of the technical committee in charge of negotiating the definition of legality within the framework of a VPA for Cameroon. It covers the following points:

— the exclusion – to the benefit of logging companies – of all the social and environmental obligations that are admitted within the certification framework but that are still not introduced in the law;

— the unification of the legal framework (without expressions such as the “main” or the “minor” laws and regulations) and the inclusion of all the national and international legal instruments that can be applied to the forestry sector;

— the guarantee that the reform of the relevant legislations will precede the implementation of the VPA

.

4 DISCUSSION: CHALLENGES AHEAD

4.1 Defining and managing “legality”

This consensus surely represents progress, highlighting the fact that civil society has been successful in establishing a number of ideas. However, many challenges are still to be taken up before reaching a good definition of legality. Among them, there are at least: (1) the management of the “original illegality”; (2) the question of the illegal wood seized and sold by the administration; and (3) the integration of the legal requirements whose related legal framework does not provide for documents proving that they have been respected.

First, there is the management of the “original illegality”. The current version of the document dealing with the definition of legal wood suggests that only non-governmental actors can act illegally. There is a presumption of legality on behalf of the administration. However, such a presumption is misleading.

Second, there is the question of the wood seized and sold by auction by the administration. According to the 1994 law[See Article 144(1).], such auctions only concern wood already logged and they are organized in order to ensure the commercialization of the wood seized by the administration because of abandonment or illegal exploitation. However, sales by auction have proliferated with the reinforcement of the donors’ vigilance with respect to the allocation process of the concessions. The practice consists in auctioning an important and fictive volume of wood, the proof of the sales being then used as a justification for the exploitation of timber up to the limit of the same volume. Incidentally, the minister of the environment has himself recognized – and condemned – the existence of these fraudulent practices: “I have noticed that various economic operators of the forestry sector carry out, sometimes with the complicity of employees of the Minister of the Environment and the Forests [MINEF], fraudulent logging in the forest, and then come to my services in order to get authorizations for the removal of the wood supposedly abandoned in the forest or in order to seek for their profit the organisation of sales by auction of abandoned wood, [a practice] that is now forbidden”. [See Circular Letter No. 0399/LC/MINEF/CAB of 30 January 2001.] In spite of this, the sales by auction have continued and continue replacing legal ways of accessing the resource (GFW, 2002). Consequently, it would be desirable – in order to discourage such large-scale illegal and unsustainable logging practices – to exclude from the FLEGT and from exports in general all wood issued from sales by auction, and to reserve it for the internal market only.

.

4.2 Verification and credibility

As we have seen, illegal activities proliferate in the forestry sector as the 1994 law was not correctly enforced and the MINEF did not benefit from enough means to ensure the monitoring of forest exploitation. Indeed, in 1998–1999, official exports reached 2.9 millions of cubic meters, while the official production was only of 1.9 millions of cubic meters (Cuny et al., 2004).

This reality has pushed international donors and buyers to demand the application of forest laws and a more efficient verification process in Cameroon. Notably, they have put several Independent Observers in charge of monitoring the allocation of the forest exploitation titles, the logging activities, and the forest concessions through remote sensor techniques.

In parallel, the Ministry of Finance has been more involved in the application of the “good governance” principles. Within the framework of the structural adjustment program and due to the need for increasing the national income of the forestry sector, this ministry has been in charge of all the fiscal responsibilities devolved to the MINEF until then. [See Decree No. 08/009/PM of 23 January 1998.] Moreover, the Securitization Program of the Forest Revenues (PSRF), created in 1999, is supposed to allow the Ministry of Finance and the MINEF to collaborate on a rigorous monitoring of the fiscal revenues of the forest sector. They are supposed to exchange information in order to allow for a better collection of the data and a more effective and harmonious detection of offences (Cerutti and Assembe, 2005). As we have seen, these control systems present some weaknesses due to the lack of capacity of Independent Observers to guarantee sanctions.

In spite of the important lessons concerning illegality, the FLEGT negotiations in Cameroon only put the MINEF in charge of the responsibility of the verification implementation. It is imperative to create a multipartite verifying structure in order to guarantee the process’ credibility. The MINEF seems to have understood this point well as it has asked the EU to associate European representatives to such a structure in charge of the verification. But the EU has declined the offer, arguing that Cameroon is a sovereign state that has to ensure legality verification on its own. The non-interference argument is inappropriate when the timber companies are European and when the history of exploitation and change in property rights dates back to European colonization.

Moreover, local communities – which have been long aware of problems – should be allowed to actively take part of the decision processes. Many crucial questions are today open and can only be addressed with local participation, such as:

• Should industrial logging activities continue in the primary rainforest? If yes, on what area should logging activities take place?

• Who should pay for reforestation?

• Who judges sustainability? The company? The state? What about the workers, local peasants, or “Pygmy” communities?

• Sustainability for whom? With what criteria?

• What is the extent of illegal logging, what is the value of official statistics?

.

The FLEGT-VPA process formally creates space for dialogue in the producing country between the parties involved (government, industry and civil society) as well as inside of the different groups. The EFI policy brief 3, What is the Voluntary partnership Agreement?, outlines the spaces for “multi-stakeholder interaction” at all stages of the VPA process: preparation, negotiation, development and implementation. [See p. 5 http://www.euflegt.efi.int/uploads/EFIPolicybrief3ENGnet.pdf] On the one hand, it seems justified to acknowledge the efforts of the administration in the dialogue with all the parties involved in the signature of a VPA. On the other hand, it is important to point out that a full and effective participation of civil society has still not been achieved, despite the inclusion of mechanisms for participation. The following breaches can be mentioned:

• Lack of full participation of civil society in all the activities led by the Cameroonian party.

• Lack of an institutional framework related to the participation of civil society. A technical commission in charge of conducting the VPA negotiations has been created, under the decision of the Minister of Forests, and allows civil society to be associated to the process. However, the institutional conditions of its participation have not been provided.

• Lack of a clear mode of decision-making within the technical commission.

• Lack of access to information and documentation for all the parties involved. This is one of the main conditions for effective participation of civil society in the process.

• Weak representation of civil society and limits on its contribution. Although civil society is represented by a group of organisations regrouped into a platform, it has only one seat in the commission and it is therefore impossible for civil society to deploy all the expertise existing within the platform.

• Confusion in the representation of civil society. Civil society has suggested, without success, that open invitations should be made so that it would be able to choose the members entitled to represent it.

• Permanence of civil society participation. This question is worrying because the technical commission that represents the only formal framework of exchange between the different involved parties will be dissolved as soon as the VPA will be signed. [See Article 6 of Decision No. 0957/ MINFOF/D/MINFOF/SG/DF of 15 November 2007.]

On the basis of this last concern, several actions have been led and have conducted to two main results related to the creation of committees. First, the government has undertaken to form a “National Monitoring Committee”, as soon as the VPA is signed, that regroups all the involved parties, including: (1) representatives of the related administrations; (2) Members of Parliament; (3) representatives of the forest districts (private holders, concessionaires and beneficiaries of the forest tax); (4) representatives of civil society organisations; (5) representatives of the private forest sector; (6) associations existing in the wood chain. Secondly, within the VPA framework, a “Monitoring Joint Committee” should be created and would ensure and facilitate the follow-up and assessment of the implementation of the VPA.

.

The pattern of extraction of forest resources, disguised as “selective logging” to the benefit of foreign companies and consumers, continues in Cameroon. FLEGT might help to stop this under certain conditions. Forest management remains today unsustainable and the forest is still the scene of many illegal practices. Indeed, illegal practices have adapted to the new rules – they became more complex and sophisticated. They can therefore give the impression to have decreased (Cerutti and Tacconi, 2008). However, this is not the case. Corporate accountability has not been implemented. Environmental and social liabilities remain outside the accounting books of companies, and outside the state’s budget. Old colonial rules changing property rights to the land and forests did not change with independence. The benefits of conservation in terms of environmental values and the provision of products and services for the local population have been sacrificed to the pursuit of monetary gain by companies that enjoyed concessions. The state has not been able or has not been unwilling to implement legislation that provides for strict zoning of forest areas and for substantial taxation of wood exports. Attempts at community co-management have not been successfully implemented.

There are now new attempts in the law and in international negotiations with the EU to reduce illegal timber exports and to secure the application of sustainability criteria in forest management and timber exports. A number of points arise:

First, the solution to this conflict involves much more that enforcement of the law, as what is considered legal is far from being in line with principles of sustainable forest management. In addition the FLEGT is flawed because (1) it is based on a presumption the state is acting legally, and (2) it entrusts the state with the monopoly of the verification process, despite the fact that there are numerous documented cases in which the administration has acted in total illegality.

Second, the FLEGT process offers an opportunity for civil society to influence the regulation of the logging sector operating in Cameroon, allowing different kinds of actors to discuss controversial issues together. In this sense FLEGT has created a space for improving participation in logging practices. However, FLEGT’s economic rationale basically remains the same as that which prevailed during the colonization period and continues today, namely to extract timber from peripheral poor regions and to export it to Europe in a pattern of ecologically unequal exchange. This “environmental injustice” arguably arises from a kind of “environmental racism”.

Third, the FLEGT does not challenge the legitimacy of Northern consumption patterns, nor does it question the legitimacy of private operators that originate from the North and that accumulate the lion’s share of the produced wealth. Nevertheless, it can be interpreted as an attempt to move towards “fair trade”, by providing instruments for verifying compliance with legal provisions, similar to the certification of wood in other international schemes.

Finally, the concept of an ecologically unequal exchange has been implicit everywhere in the case. At this stage, it is not clear to what extent the FLEGT process is really able to challenge this situation. While one of the best ways to establish extractive processes that are more equitable is to foster democratic deliberation, or what is sometimes vaguely referred to as “participation”, this can only take place within more balanced power relations – a fact that is clear from the idea of conflicting languages of valuation. A democratic process would undoubtedly result in improvements in the redistribution of revenues and legal recognition of customary tenure arrangements, as well as increased timber prices.

.

Abega, C.S. 1998. Pygmées Baka, le droit à la différence. Yaoundé: Presses de l’Université Catholique d’Afrique Centrale.

Agir Ici and Survie. 2000. Le silence de la forêt: réseaux, mafias et filière bois au Cameroun. Dossiers Noirs n°14. Paris: L’Harmattan.

Altvater, E. 1993. The future of the market: an essay on the regulation of money and nature after the collapse of “actually existing socialism”. London: Verso Books.

Arnold, J.E. 1998. Managing forests as common property. FAO Forestry Paper 136. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

Auzel, P., Fomété, T., Odi, J., Owada, J.-C. 2003. Evolution de l’exploitation des forêts du Cameroun: production nationale, exploitation illégale, perspectives. Présentation réunion DFID, MINEF, Banque Mondiale et FMI, Yaoundé.

Bergh, J. van den and Biesbrouck, K. 2000. The social dimension of rain forest management in Cameroon: issues for co-management. Tropenbos-Cameroon Series 4. Kribi: The Tropenbos-Cameroon Programme.

Berkes, F. 1999. Sacred ecology: traditional ecological knowledge and resource management. Philadelphia: Taylor and Francis.

Betti, J.L. 1996. Étude ethnobotanique des plantes médicinales de la réserve de faune du Dja (Cameroun). Yaoundé: Rapport ECOFAC/Cameroun.

Biesbrouck, K. 1999. Bagyeli forest management in context. Tropenbos-Cameroon Reports 99-2. Kribi: The Tropenbos-Cameroon Programme.

Bigombé Logo, P. (Ed.) 2004. Le retournement de l’Etat forestier: l’endroit et l’envers des processus de gestion forestière au Cameroun. Yaoundé: Presses de l’Université Catholique d’Afrique Centrale.

Bunker, S.G. and Ciccantell, P. S. 2005. Globalization and the race for resources. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Bunker, S.G. 1985. Underdeveloping the Amazon: extraction, unequal exchange and the failure of the modern state. Chicago: University Chicago Press.

Cabeza-Gutés, M. and Martinez-Alier, J. 2001. L’échange écologiquement inégal. In: Damian, M. and Graz, J.-C. (Eds.), Commerce international et développement soutenable, pp. 159-185. Paris: Economica.

Centre pour l’Environnement et le Développement (CED). 2002. Les attributions des UFA de juillet 2000: commentaires et propositions pour la réforme. Yaoundé: CED.

Cerutti, P. and Assembe. 2005 Cameroon Forest Sector-Independent Observer-Global Witness End of contract project review.Yaounde, Cameroon, Department for International Development (DFID)

Cerutti, P and L. Tacconi, 2006. “Forest illegality and livelihoods in Cameroon” working paper 35. Bogor. Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), available at htp://www.cifor.cgiar.org/publications/details?pid=2108

Cerutti, P. and Fomété, T. 2008. The forest verification system in Cameroon. In: Legal timber (Ed. CIFOR), pp. 135-262.

Cerutti, P. and Tacconi, L. 2008. Forests, illegality and livelihoods: the case of Cameroon. Society and Natural Resources, 21(9): 845-53.

Collomb, J.G. and Bikié, H. 2001. 1999-2000 allocation of logging permits in Cameroon: fine-tuning Central Africa’s first auction system. Yaoundé: Global Forest Watch.

Cuny, P., Abe’ele, P., Nguenang, G.-M., Eboule Singa, N., Eyene Essomba, A. and Djeukam, R. 2004. Etat des lieux de la foresterie communautaire au Cameroun. Yaounde: Ministry of Environment and Forests.

de Blas, D.E., Ruiz Pérez, M., Sayer, J.A., Lescuyer, G., Nasi, R. and Karsenty, A. 2008. External influences on and conditions for community logging management in Cameroon. World Development, 37(2): 445-56.