Waste Crisis in Campania, Italy

Authors: Lucie Greyl, Sara Vegni, Maddalena Natalicchio, Salima Cure and Jessica Ferretti

Download case study as pdf-file.

.

2. A Brief History of the Campania Waste Crisis

2.1. The First Regional Waste Emergency Plan

2.2. The Second Regional Waste Management Plan: FIBE and Ecoball

2.3. The FIBE – Impregilo Affair

2.4. The answer to the emergency: Decree 90

3.1. Market Mechanisms of the Illegal Waste Industry

4. The Externalities of Campania’s Waste Crisis

4.4. Social impacts: civil society mobilisation

5.1. The conflict as a Post Normal Science problem

5.2. Emergency management and abuse of power

5.3. Corporate Influence and Interrelations: The Role of Impregilo

5.4. Corruption and Ecomafia Infiltration of Urban and Industrial Waste Management

5.5. Waste production and treatment

5.6. Exploring causality, consequences and responses

5.7. Campania as a case of Environmental Injustice

.

.

From 1994 to early 2008, the region of Campania in south-west Italy existed under a formal State of Emergency, declared due to the saturation of regional waste treatment facilities. There is growing evidence, including a World Health Organisation (WHO) study of the region, that the accumulation of waste, illegal and legal, urban and industrial, has contaminated soil, water, and the air with a range of toxic pollutants including dioxins. A high correlation between incidences of cancer, respiratory illnesses, and genetic malformations and the presence of industrial and toxic waste landfills was also found. The Government has been unable to resolve this crisis, adopting measures that have only increased public unrest, exacerbating the conflict. Local communities continue to organise and protest, risking arrest in order to be heard by a Government that has so far excluded them from decision-making processes. Meanwhile the management of waste has worsened: from the failure to separate dry from wet waste and the resultant inability to produce compost (necessary for the regeneration of contaminated land) to the continued production of the inaccurately named “ecoballs” that have continued to accumulate due to delays in the construction of incinerators. These delays have necessitated the creation of new stocking areas, the re-opening of old landfills and the creation of new ones. Although Illegal waste management is currently one of the most urgent environmental issues in Italy, public opinion and the media remain silent on the matter.

Keywords: Hazardous waste, Ecomafia, externalities as cost shifting success, post-normal science, “Zero waste”, incinerators, Lawrence summer principle, DPSIR (Driving forces, Pressures, States, Impacts, Responses), corruption, democracy crisis, EROI

Figure 1 : The region of Campania in Italy (Source: http://www2.minambiente.it)

.

The region of Campania in south-west Italy (Figure 1) is divided into 5 provinces: Naples, Avellino, Benevento, Caserta, and Salerno. About 25% of all of protected areas in Italy are found within this region, the capital city of which is also Naples. There are currently 4 State Natural Reserves, 8 Regional National Parks, 4 Regional Natural Reserves, 106 Sites of Community Interest and 28 Special Protection Zones. Campania is notable as the most densely populated region of Italy, and also one of the nation’s poorest regions.

Campania´s waste crisis was first revealed to the world through the images in the news of the city of Naples invaded by waste. This emergency was publicized as a waste disposal problem while the real problem remained hidden to the public. Indeed, if international media coverage is to serve as an indicator, the waste conflict in Campania was fully resolved as of July 18, 2008, as a direct result of waste management measures implemented under Berlusconi (The Economist, Feb 26th 2009). However, closer examination of the waste crisis reveals a much more complex picture. For more than two decades the illegal and/or inappropriate treatment and disposal of urban and industrial waste has contaminated of the region’s soil, superficial and underground waters, and atmosphere, threatening every single living thing and being.

There are various forces responsible for Campania´s waste crisis: damaging cultural behaviours, illegal activities of the Camorra (the name of a dominant Naples mafia clan), and criminal behaviour on the part of politicians and public administrators, company managers and freemasons. Campania´s waste management cycle has been infiltrated by an Ecomafia (a network of criminal organizations that commit crimes causing environmental damage) that have developed an alternative illegal and polluting waste management market for “treating” both local and other region´s urban and industrial waste.

This case study presents Campania´s waste crisis, showing both the legal and illegal aspects of the story. We show what has happened in the past and what still continues, indicate where responsibility lies and outline the social, environmental and economic externalities produced by the current waste management in Campania. Finally, through the lenses of ecological economics, this paper will analyse the main issues underlying the case with a view to better understanding this complex conflict situation.

.

2. A Brief History of the Campania Waste Crisis

The “emergency” we are currently witnessing, presented by the media as a urban waste management issue, is much more complex than it seems. The contamination affecting the region is the result of corrupt waste management practices enabled by the use of subcontracts to private consortiums, lack of power to enforce the law and by the persistence of an illegal waste management market that started decades ago with the treatment of harmful toxic waste produced by northern Italian industries.

It all began in 1989, when Italian politicians of the Liberal party, members of the Freemasonry, and heads of the Casalesi clan met in Villaricca, in the province of Caserta. The purpose of the meeting was to define the different roles and compensations for waste management. The Freemasonry were in contact with northern Italian industrialists interested in getting rid of hazardous waste at below-market rates, and the Camorrist clan offered to provide these services through its own transport company, authorised by the Regional Councillor of Ecology from the Liberal party, Raffaele Perrone Capano.

Initially, waste – both urban and hazardous – was simply transported to and abandoned in illegal landfills. Then, as the market grew, the system became more complex and extensive, resembling the current system in which waste is sent to Campania from where it transits to several storage and treatment sites until it is buried or dumped on land or in watercourses. Only on paper does this waste receive “treatment”.

No-one has been able to stop the mafia traffic. Public institutions tried to develop new legal frameworks for monitoring waste management, but these efforts failed to lead to any real improvement of the situation. In February 1993 the first Regional Waste Management Plan was approved in order to reduce the use of landfills in Campania by 50%. However, this measure was not effective and when landfills were saturated in February 1994, the State of Emergency was announced.

.

2.1. The First Regional Waste Emergency Plan

With a view to resolving the crisis, the Italian government appointed Naples Prefect, Umberto Improta as the first “Extraordinary Commissary for the Waste Emergency” while the regional administration was asked to prepare a waste management plan. The Prefect was unable to handle the emergency and in March 1996, the task of resolving the crisis was handed over to the President of the region, Rastrelli. This Prefect maintained responsibilities for daily waste management only, creating 6 ATOS, (areas for locating waste treatment facilities) and preparing a sorted waste collection plan for the collection of up to 35% of solid urban waste. The plan failed.

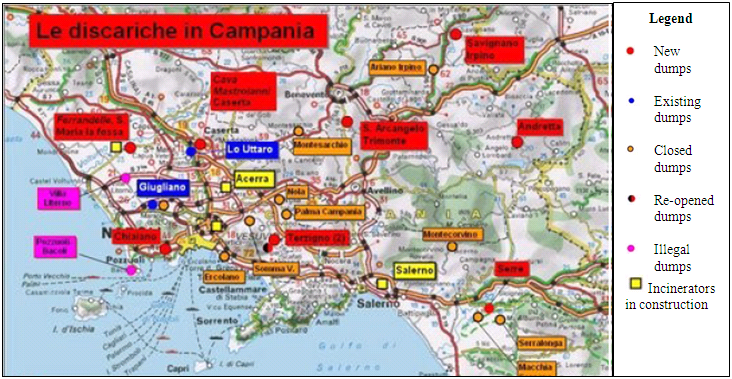

In February 1997, three years after the beginning of the State of Emergency, the Ronchi Decree (nº.22) was approved, incorporating the main European waste management regulations into Italian law. The Decree first prioritised the implementation of waste production prevention policies, followed by waste collection, recycling, re-use or combustion measures. Then the Decree made provisions for the limitation of waste disposal to prevent health and environmental contamination risks. It also established obligations for waste producers and managers to identify and register transport, and to provide environmental declarations. Unfortunately, the Decree had no impact in practice. Because waste treatment was dysfunctional the need for new waste disposal sites kept growing to the point where new landfills were created and some old ones were reopened (Figure 2). Increasing pressure to dispose of waste lead to an unleashing of local community protest.

.

Figure 2: Landfills in Campania in 2008 (Source: Ecoalfabeta 2008)

top.

2.2. The Second Regional Waste Management Plan: FIBE and Ecoballs

On March 31st, 1998, the Italian Minister of Internal Affairs, Giorgio Napolitano (now the President of the Italian Republic), fostered a plan to modernize the Region´s waste management practices. Selective waste collection was to be introduced in order to reach a 35% reduction of solid urban waste (SUW). Commissary Rastrelli was given four months to write a tender for a 10-year urban waste management plan for Campania.

The tender included the construction of seven RDF (Refuse Derived Fuel, also referred to as “ecoballs”, formed of packed waste of high calorific value to be burned for energy production) infrastructures, and two thermovalorizers, which are incinerators that use 50 year-old technology to produce energy by burning waste of high calorific value (particularly ecoballs). The main criteria used by the Commissariat to select the winning bid was the speed of construction and the minimization of costs, as a quick solution was desired for dealing with waste.

With Decree nº 16 on April 22nd 1999, FIBE was provisionally awarded the tender for waste management for the province of Naples. FIBE was an A.T.I. (a temporary company association) composed of the following companies: Fisia Italimpianti S.p.A., Babcock Kommunal Gmbh, Deutsche Babcock Anlagen Gmbh, Evo Oberhausen AG, and Impregilo S.p.A. Competing bids offered better infrastructures, superior technologies, and lower pollution/environmental impacts, but proposed a treatment cost of 0.06 € /kg with a 365-day construction period. FIBE in comparison offered a 0.04 € /kg treatment cost, and a construction period of 300 days. On the 20th of March 2000, with Decree no. 54, the Commissar officially awarded the contract for urban waste management for the entire region to FIBE.

.

Figure 3: RDF production plants in Campania (Source: Coreri, International Waste Conference February 17, 2009)

Figure 3: RDF production plants in Campania (Source: Coreri, International Waste Conference February 17, 2009)

.

FIBE built seven RDF production facilities (see Figure 3), at a cost of over 270 million €, with one of the two planned incinerators financed by EU funds. The Acerra incinerator has been in operation since March 2009, while the second facility, located in Santa Maria della Fossa (Figure 4) is still on stand-by. According to the tender, all solid urban waste collected was to have been treated in RDF plants to become ecoballs (32%), compost (33%), and ferrous waste (3%) with only 14% disposed of in landfills. The ecoballs produced and stored during the construction of incinerators, as specified in Napolitano’s decision, were to eventually have been burned in thermovalorizors for the generation of energy from combustion.

.

Figure 4: Landfill at Santa Maria della Fossa (Source: A Sud)

.

A highly controversial aspect of the agreement made with FIBE was that the consortium was given sole authority to select the construction sites of the infrastructures, completely independently of public administrative bodies. This led to speculative activities in the rental of land by the Camorra, as well as numerous environmental and health impacts, as legal requirements for Environmental Impact Assessments (EIA) prior to infrastructure construction were derogated by the Commissary through the use of his extraordinary powers granted under the State of Emergency. EIAs were replaced by “Environmental Aspect Valuations”, and then, by “Environmental Compatibility Valuations” which had very little bearing on decision-making processes.

The extraordinary powers granted to the Commissary enabled rapid decision-making but also created a lack of transparency which enabled the taking of many illegal decisions. This was certainly the case in the choice of waste transport companies and the control of ecoball stocking and landfill sites, which were (not coincidentally) based in mafia territory. Another significant decision of the Commissary was to exclude municipalities and other local entities from waste management plans (Commissariat Decree 319 of 30-09-2002).

Since 2001 there have been perennial “Emergencies within the Emergency”. With RDF storage sites filling to capacity and the construction of the incinerators proceeding very slowly the Commissary has had to help FIBE find new storage sites for the inert and humid parts of treated waste. The region has been obstructed by waste on numerous occasions, and is still blocked frequently today with streets full of garbage. Each time one of the seven RDF sites is closed, for reasons ranging from regular controls, mafia interference and magistrates’ enquiries and sequestrations, the collection of waste slows down, waste fills the streets, and old and new dumpsites are opened once again to store the large quantity of ecoballs waiting to be burned in incinerators under construction.

.

2.3. The FIBE – Impregilo Affair

A critical issue of the waste treatment process as it has been conceived in Campania is the poor quality of RDF, or ecoballs derived from waste (see Figure 5). The chemical laboratory controlling the RDF plants was the property of Fisia, a member of the FIBE consortium. Judicial sequestrations have shown that infrastructures were not able to separate the various types of waste and the RDF produced was practically impossible to burn. In these ecoballs, percentages of arsenic over the legal limits were found, together with whole objects (e.g. entire wheels with tire and structure intact). The humid fraction was furthermore too wet for incineration in thermovalorizors. RDF was supposed to contain a maximum

humidity of 15%, but it was found to contain more than 30% and could not be burned under European regulations or Italian laws firstly because of the highly toxic emissions it would produce, and secondly, because of the negative EROI (Energy Return On Investment), as the amount of energy produced by its combustion would have been lower than the amount needed to actually burn the waste.

Numerous police investigations looked into the quality of ecoballs piled in stocking areas and production facilities. A major judicial enquiry known as the “Operazione Rompiballe” was led by Magistrates Giuseppe Noviello and Paolo Sirleo in 2002, after public condemnation by Senator Tommaso Sodano of the Communist Refoundation Party. RDF sites were put under preventive sequestration by a decision of the Naples court on the 12th of May 2004, but the management of these sites was handed back to FiBE – Impregilo on the condition that it abided by the law and its contract. FIBE however violated these conditions repeatedly. The contract for example reinforced FIBE’s obligation to guarantee the incineration of RDF in existing plants for energy production while waiting for the completion of the Acerra plant, but FIBE failed to even treat ecoballs for RDF production as required by law.

On January 26th, 2006 a law recognised the responsibility of FIBE – Impregilo for the waste management crisis, stating that the company should continue to manage the waste treatment facilities and stocking sites until a new consortium was selected. Two European tenders were launched but to this day, none have been awarded. In June 2007, the European Commission initiated an infraction procedure for Campania’s waste management. The procedure is still in process and it is anticipated that it will lead to monetary sanctions against Italy. Also at the end of June 2007, Naples’ magistrates sequestered a total of 750 million € worth of Impregilo assets, imposing a one year interdiction on dealing with any public administrative bodies on waste management.

The “Rompiballe” inquiry concluded at the end of July 2007 with a request to bring about 30 persons including public administrators and entrepreneurs to trial. Three magistrates affirmed that owing to the inadequacy or lack of waste transformation facilities, the waste cycle as it had been conceived in the contract signed with the Impregilo could never have worked. Both Impregilo and Bassolino, who was the Commissary for the waste emergency between 2000 and 2004, hid the situation even though they had been informed of irregularities: the RDF plants were built on waste management sites different from those projected, the ecoballs were irregular and the quality analyses were falsified.

On August 8th 2007, the Court ordered the confiscation of nine sites where three million tonnes (t) of Campanian low-quality ecoballs were being stored. Judge Rosanna Saraceno, in charge of the preliminary enquiries, deemed the stocking sites located between the provinces of Naples and Caserta illegal controlled landfills. According to judges, RDF should have been kept in prepared dumpsites instead of stockpiled, as they violated the chemical composition required by law. FIBE, in charge of the stocking facilities, was ordered by the Courts to treat the ecoballs so that they could be burned under existing norms. It was estimated that this process would cost FIBE about 600 million €.

This trial is still ongoing and scheduled sessions are frequently cancelled. So far, judges have prosecuted personalities such as the President of Campania, Commissary Antonio Bassolino (2006-2007) Guido Bartolaso, the Head of Civil Protection since 2001, the Sub-Commissary of the period, Claudio De Biasio, the ex-manager of Impregilo and administrators of companies of the consortium Armando Cattaneo, Enrico Pellegrino (FIBE) and Pier Giorgio Romiti (Impregilo), as well as other important public administrators.

.

Figure 5: Ecoball storage (Source: Ansa)

Figure 5: Ecoball storage (Source: Ansa)

.

.

2.4. The answer to the emergency: Decree 90

In 2008, with waste treatment capacity beyond saturation, the streets of the provinces of Naples and Caserta became re-filled with waste and another State of Emergency was declared. In May 2008, in order to deal with the crisis, the national government implemented Decree 90, the most recent and most powerful ruling approved in Campania for waste management. Unfortunately it is also the least respectful of environmental and human rights. This law centralised decision-making power in one person: the Head of Civil Protection, Guido Bertolaso, who was prosecuted under the FIBE – Impregilo affair. As Emergency Commissary he was able to derogate any law he judged necessary for implementation of the Decree. Waste treatment facilities (built and in construction) were thus designated “areas of strategic national interest” and militarised.

The Decree planned the construction of 9 new landfills in the region and 4 incinerators; two in the province of Naples (one in Acerra and the other in the city of Naples ), one in the province of Salerno, and one in Caserta (Santa Maria la Fossa). No tender was ever released for the construction of these plants. Instead the company was personally selected by Bertolaso, favouring the interests of the same lobbyists that created the waste emergency in the first place, illustrating that no real measures were taken under this Decree to stop corruption and crime in waste management.

The incinerator of Acerra for example (Figure 6), which opened in March 2009 was built by Impregilo under Decree 90, despite the ongoing trial against the company and without the preparation of an environmental impact assessment as required by law. This incinerator was authorised to burn several types of waste, including very low quality ecoballs produced from 2005 by FIBE. Moreover, the environmental observatory established to control the incinerator is composed of the same entities that were involved in its design and implementation: the Ministry of Environment, the Campania Region, the province of Naples, the Acerra, San Felice and Cancello City Councils, Campania’s Regional Environment Protection Agency (ARPAC), “Napoli 4”, a local health agency, and one epidemiologist.

Once Acerra’s incinerator reaches its full functioning capacity, its management will be handed over to the Asian – A2A consortium. This consortium has also been given responsibility by Bertolaso for the construction and management of the Naples incinerator. At the moment, the Santa Maria della Fossa incinerator has not been built as the sites designated for its construction have been sequestered from FIBE.

.

Figure 6: The incinerator at Acerra under construction (Source: http://wildgretapolitics.wordpress.com)

.

The measures and management plans implemented so far by authorities have so far been done so with disregard for environmental and health protection. Despite decades of investment and construction of a huge infrastructure complex, the management of waste treatment in Campania is still ineffective. In other European countries this would seem inconceivable but unfortunately in Italy this is quite common, and as the many enquiries and trials have shown there are two main reasons for this: corruption and mafia.

Since the beginning of the waste problem in Campania, an illegal waste market has evolved as mafia have infiltrated local and regional waste management. This explains, for instance, the presence of toxic waste within the ecoballs produced by the RDF plants. Campania is one of the poorest regions in Italy and many municipalities do not have sufficient resources to develop their own public waste management service companies, so clans easily enter into these businesses, “creating” companies and working under their auspices. Favouritism towards mafia-related companies is a common practice in Campania and, judicial investigations have revealed evidence of close links between the mafia and authorities at all levels, from the Emergency Commissariat to individual municipalities.

The Anti-Mafia Control Office declared that between 2001 to 2003, only 3 of 21 companies in charge of waste collection in the province of Naples were “clean“ of any mafia links. However, the identification of such links by Judicial investigations is not enough to stop the phenomenon, as companies branded as having mafia ties often change their names, administrators, and legal representation while keeping the same office, the same telephone and fax, and even the same trucks and drivers.

In addition to mafia infiltration of legal waste management operations, there also exists a parallel illegal hazardous waste market, which handles waste coming from all over the country, especially from northern industries. Campania is propitious for these activities as the highest-ranking region in Italy for environmental crime, where 14.7% takes place. Moreover, illegal waste treatment is a very lucrative business, with an estimated national value of 7 billion € in 2008. Italy holds the record for waste “disappearance” (after its record for production) with about 31 million ts of hazardous waste vanishing without legal treatment (Legambiente 2008, 2009).

.

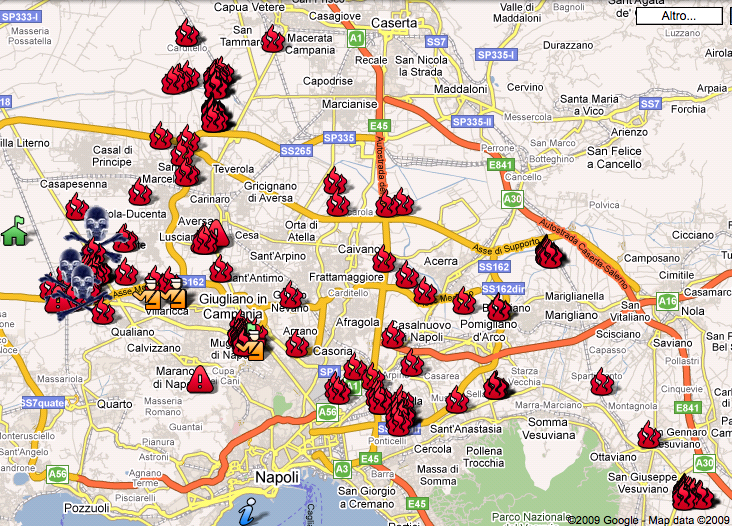

Figure 7: Illegal fires in the Provinces of Naples and Caserta (Source: www.laterradeifuochi.it)

.

As a result of this process, the territory of Campania has been invaded and poisoned by waste for about 20 years. The province of Caserta is the most affected area because its geography of vast plains and numerous natural caves is particularly well-suited to hiding and containing waste. The province is also under the control of the powerful Casalesi clan, pioneers of the trade. The hinterland of the province of Naples is another important area of waste criminality. The Land of Fires, or “Terra dei Fuochi”, an area between Giugliano, Qualiano and Villaricca is sadly notorious for its ever-rising columns of smoke from illegal waste burning. This is a frequent phenomenon in Campania where there are about 17 illegal fires every day (see Figure 7). The province of Salerno also registers an increasing number of officially recognised illegal landfills. (Legambiente 2001, 2005, 2008)

.

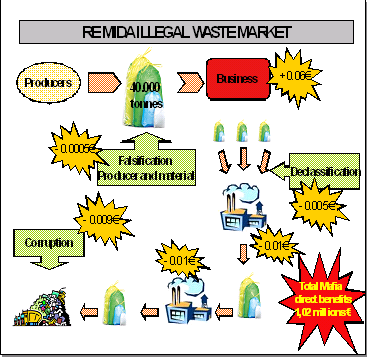

3.1. Market Mechanisms of the Illegal Waste Industry

The business of illegal waste management is based on the transport and ”treatment” of hazardous waste as well as on the infiltration of the local urban waste management cycle. It is a major sector of organised criminal activity, especially the industrial waste market with its smaller infrastructure needs and higher profits. The illegal waste market is attractive and gains new clients every day (OAL, 2008, OAL, 2007).

One of the main characteristics of the illegal market consists of the creation by mafia of “clean” companies for waste management at all level of the cycle. These are funded and promoted in the legal market and used for illegal traffic (OAL, 2008, OAL, 2007). Infiltration at all levels of the waste cycle allows mafia to control every detail. For example, waste received from producers can be re-categorised, changing its official toxic status. Sometimes producers do not even declare their waste generation figures so mafia-related companies make the declarations themselves. The mafia also manage transit to storage areas or to treatment facilities, and is therefore able to falsify documents of waste classification, intermediary “treatment” and final “treatment”.

.

Tips for illegal waste management

Illegal waste treatment methods are very inventive. From “traditional” large open air dumps characteristic at the birth of the illegal waste market at the end of the 80’s, to other numerous methods:

- burying waste in cultivable areas, roads, construction yards, etc. and in natural caves;

- sending industrial hazardous waste to non-hazardous urban waste treatment facilities or other non adapted treatment sites;

- abandoning hazardous waste derived from shredded urban waste on land undergoing decontamination, in the countryside and in natural areas such as the Vesuvius crater;

- spreading of false fertilizers and composts containing toxic substances;

- adding waste to the production of cement, metals and asphalt;

- diluting waste and disposing of it in sewage systems, rivers and the sea.

(Source: Legambiente 2005, 2007, 2008)

.

The waste “treated” on the illegal market is unbelievably diverse. It can be basic urban waste but also street sweepings or old bills from the Bank of Italy. All sorts of hazardous waste of varying toxicity is also treated: toxic powders and mud, soil mixed with highly toxic substances such as arsenic, mercury, and all sorts of metal toxic components, hospital waste, sewage waste, industrial mud and oils from hydrocarbons mixed with ground urban waste, used automobiles, inert materials, soils from graveyards and even special paper tissues for cleaning bovine calves. What matters to dealers is not the waste itself but the opportunity for profit it represents. (Legambiente 2005)

The illegal waste management market is a “real market” with profits and prices still in Italian lire for every kind of waste and service. Industrial waste treatment prices (0.52€/Kg) are very low, equalling roughly half of legal market prices. In contrast, prices for urban waste management (0.08€/Kg) are higher than those of the legal market, but there is no shortage of clients thanks to the waste emergency. Prices vary across the various categories of waste, also taking into account the composition of materials (one price for the “clean” part and another price for the toxic part), potential operative difficulties and clients’ needs.

.

The Re Mida case: a Micro analysis of illegal waste market

The Re Mida case allows a closer insight into Campania´s illegal waste market. In 2003 a police operation revealed this as one of the biggest waste traffic operations in the region, controlled by the Casalesi clan. During a period of 6 months, 40,000 t of waste were transported from the north of Italy to the south, mainly to the Giuglianese area, and to the northern area of the province of Naples. This was mostly hazardous industrial waste, although there was also urban waste present. The waste had come from Lombardia, Toscana, Piemonte, Veneto and also Sicily, and was being buried in caves in the Garganese area, for ”treatment” to produce compost for cultivable land in the north of Naples.

The Re Mida case (Figure 8 ) involved actors from all sectors: civil engineering, transport, chemistry, infrastructure management, intermediate’ services, etc.. Through mafia intermediaries the waste was “exchanged” at an average cost of 0.06 €/Kg. Then it was transported as random material from its origin to Campania through falsified documents on the materials’ transport and origins, at a cost of about 1 lire or 0.0005 €/Kg (15 000€/Month). Once the waste arrived in Campania, it was declassified with the complicity of analysis laboratories, at a price of 10 lire or 0.005€/Kg to bring it in line with the normative requirements of the storage and “treatment” structures it was to be sent to. Then the waste

was “transformed” and “treated” in a couple of infrastructures before being sent to its final destination. In exchange for “treatment” (or in this case “transformation” into compost or soil for decontamination), the company charged 20 lire or 0.01€/Kg. The final burial of waste was made possible with authorization from complicit local public administrators, or by corrupt land owners at a price of 0.009 €/Kg, or 0.008 €/Kg if the person involved was connected to the main “business” dealer.

The total business was estimated at 3.3 million €, plus tax evasion worth 500.000 € (in 6 months) for 40 000 t of waste which if treated legally would have cost 6.2 million €. The last part of the police operation resulted in the sequestration of two caves, in Quarto, Naples and in Viterbo, Lazio, where 2000 t of hazardous waste were buried, for a profit of 100 000 €. (Legambiente 2005, 2007, 2008)

.

Figure 8: Re Mida illegal waste market flows (Source: A Sud)

.

.

4. The Externalities of Campania’s Waste Crisis

It is difficult to completely and comprehensively assess the externalities of contamination from urban and hazardous waste in Campania, as some regions are well documented but others are incompletely, or have not at all been studied. One of the major factors affecting the quality of soil and other environmental components like watercourses and underground water reservoirs is the contamination of specific locations of waste storage facilities, especially in Naples and Caserta, the most affected provinces. In general, though, urban areas are more monitored than rural and industrial ones.

.

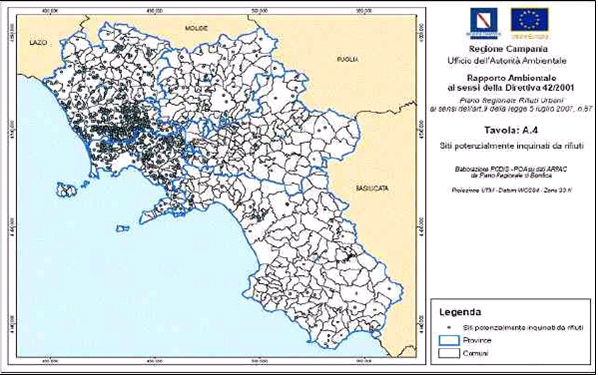

In Campania, the Commissariat initiated the contaminated sites census in 1996 and by 2008 it was estimated that there were as many as 2551 sites contaminated in the region (Figure 9). The province of Naples registers the greatest number, 1186, of which 1011 are private and 175 public areas. One of the most affected areas of the province is the so-called “Lands of Fire“, comprising the 3 Napolitano municipalities of Qualiano, Giugliano and Villaricca. For ten years, inhabitants have witnessed and paid for the consequences of daily illegal waste burning. Of the 39 landfills in the area, 27 are believed to host toxic waste. In the last 5 years, illegal landfills have increased by 30% (Legambiente, 2008).

In Italy there are 55 national protected areas, six of which are in Campania and contaminated: the Domitio-Flegreo and Agro Aversano Littoral, Bagnoli-Coroglio, the Vesuvius Littoral and the Sarno and Regi Lagni Rivers. The management of national protected areas is directly controlled by the Environmental and Territory Guardianship Ministry. The typology of contaminated sites is classified as follows: 13% are caves used as illegal landfills (leading to soil and water contamination), 12% are water reserves and 75% are landfills (ARPAC, Legambiente 2008). Biodiversity research in these areas has been limited to specific systematic groups; nevertheless, the risk of extinction of some species of flora and fauna is certain due to soil and water contamination from illegal dumpsites. It is relevant here to emphasize the threat of the re-opening of dumpsites planned in the Vesuvius national park.

.

Figure 9: Contaminated sites in Campania (Source: ARPAC 2008)

.

.

Campania’s ecological footprint

Current levels of human pressure exceed the biological capacities of the territory, which also has the highest levels of soil consumption in Italy. Soil use in urban areas quadrupled between 1960 and 2000, and was accompanied by a population increase of 21%. Other environmental pressures come from the ageing of the agricultural workforce and the low level of uptake of this work by younger generations.

The Ecological Footprint of an area is a measurement of how resource use exceeds environmental limits. The area required to meet the production and consumption needs of the population of Campania, and for the assimilation of waste produced in there has been estimated at 15 times greater than the region’s resource base can actually support (G. Messina, Mia Terra, 2009).

.

The Campania Mortality Atlas (2007) published by the Regional Epidemiological Observatory showed that from 1998-2001 the first cause of illness was cardiovascular related (40% of men, 50% of women), and the second one related to tumours (30% of men, 21% of women). The first cause of mortality for young people was tumours, data that can be interpreted as being directly linked to exposure to contamination from waste. Respiratory illnesses like bronchitis and asthma are also increasing.

The presence of waste has frequently been recognised as an important health risk. In 2004, the Department of Civil Protection implemented a study on waste impacts in Campania. The project was coordinated by the World Health Organisation’s European Environmental and Health Centre with the participation of the National Research Council (Clinic Physiology Institute – Epidemiology department, Pisa), the High Institute of Health (Department Environment and Prevention), the Regional Epidemiological Observatory, ARPAC, the Campania Tumour Record, the Campania Congenital Malformation Record and the Local Health Agencies of the territories involved.

.

Figure 10: Illegal landfill in the province of Caserta (Source: A Sud)

.

In the first phase of the project, data from the Mortality Epidemiological Observatory for the years 1994-2001 and from the Campania Congenital Malformation Record for 1996-2002 were gathered for the 196 municipalities of the provinces of Naples and Caserta (Figure 10), where the highest concentrations of illegal dumpsites and landfills are found. Twenty types of tumours and 11 typologies of congenital malformation described in the scientific literature were found and linked to the presence of dumpsites and incinerators. In the second phase of the study, the landfills and dumps of the two provinces were mapped and studied, with 226 sites, most of them illegal, identified and classified according to the level of risk present.

In the last phase of the research, the health and environmental data were analysed to specify the links between contamination from waste and the increase of some health issues. It showed statistically relevant correlations between health and waste, confirming the hypothesis that the high rates of mortality and malformation are concentrated in areas contaminated by waste. Increases of 9% in deaths of men and 12% in women as well as an increase of 84% of lymphoma and sarcoma tumours of the stomach and lungs, and genital malformations were measured. Still, as the data is considered incomplete and inaccurate, the cause/effect relation has not been certified.

.

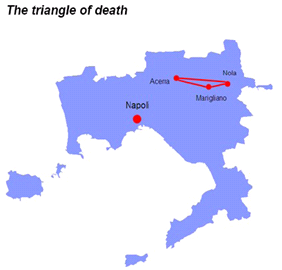

Figure 11: The Triangle of Death in Naples (Source: Wikipedia adapted from Senior and Mazza 2004)

.

Some areas are more affected by waste than others. The Napolitan area between the municipalities of Acerra, Nola and Marigliano has become known as The “Triangle of Death”, due to increases in cancer and mortality in recent years (Senior and Mazza, 2004). In the Land of Fires area (Figure 11), cancerous tumours have also increased by 30% in the last five years, proportionate to the number of illegal landfills.

Not only is the population in direct contact with waste and its airborne emissions, contamination has also affected local sources of water and food production, creating health problems as well as economic issues for the farmers of the region (Legambiente 2008).

.

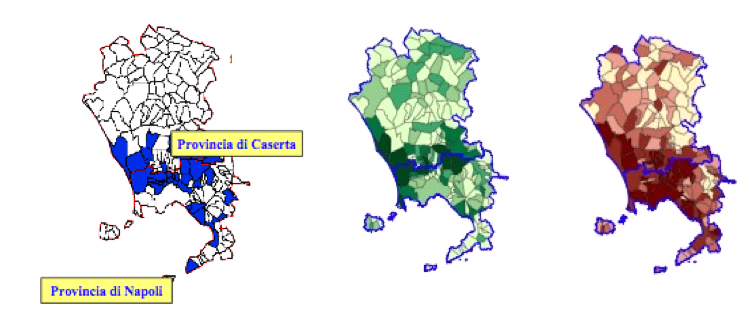

The Provinces of Caserta and Naples

The most affected zones are the areas of north-east Naples’ and south-west Caserta which mark the border between the two provinces. In their 2004 study the Department of Civil Protection created municipal-level synthetic vulnerability indicators (Figure 12), dividing the 196 municipalities of the two provinces into 5 groups of risk. Combined with another “socio-economic deprivation” indicator the analysis revealed that the most affected populations by contamination were also shown to be the most economically disadvantaged.

If we compare the maps below (in which increased colour intensity corresponds to the strength of indicators) with the map of possibly contaminated sites in Campania (Figure 9) we can see a clear correlation between the geographical distribution of illegal waste treatment activities, poverty and disease. High population density means more intense anthropogenic pressure on the environment, and these areas are also particularly affected by a lack of basic education and poverty. These socio-economic conditions reflect weak social economic and environmental policies that have lead to environmental destruction and deteriorating health conditions.

.

Figure 12: Rates of mortality and deformities, risk of exposure and socio-economic deprivation in Caserta and Naples provinces (Source: Department of Civil Protection, 2007)

top.

Campania is an agricultural region, very productive and highly specialised, and generally based on a model of extensive cultivation. Fruit and vegetables are mainly produced, but buffalo breeding for mozzarella production is also important. In 2006 Campania produced 34.000 t of mozzarella, about 80% of national production. Campania also produces about 324 traditional products and 28 certified products of Protected Designation of Origin or Protected Geographical Indication. In 2007, there were 120.000 persons employed in agriculture and 41000 in the agricultural industry in Campania. Nearly 80% of farm work is done on family farms so agricultural production units are very small (3.6 hectares of average). Campania’s total agriculture production contributes an added value of 2.4% (compared to the national average of 1.8%) to national GDP. Its rate of productivity at 4000€/ha is almost double the national average, and is ranked second highest in the nation. This is a figure that has doubled in the last decade (Messina, 2009).

Land degradation and desertification is increasingly affecting hilly and mountainous areas, coastal dunes, and established traditions of farming. Levels of organic matter in Campanian soil are alarmingly low, requiring the urgent establishment of a strategic programme for its remediation.

The food production system in Italy is very vulnerable because of waste contamination: the presence of dioxins has suppressed cattle rearing and globally the sale of food products has decreased. The waste policies of Campania are seen as creating a Culture of Death that is leading to the disappearance of rural cultural and traditional food production, involving not only important economic externalities but also inflicting a cultural loss.

.

4.4. Social impacts: civil society mobilisation

In response to the growing presence of waste and its externalities, civil society has mobilised in local grassroots committees and associations. While committees and associations worked in isolation initially, in more recent years efforts have become more co-operative and network- based.

The Campania 0 Waste Movement, composed of two main networks, the Health and Environment Campania Network (Rete Campania Salute Ambiente) and the Regional Campania Waste Coordination (Coordinamento Regionale Rifiuti della Campania) is now struggling for a new, and drastically different Waste Management Plan, one that is participatory, agreed by consensus, controlled by communities concerned with public health, and opposes incinerators and mega-landfills. These networks meet in assemblies and have scientific committees and thematic groups addressing issues and formulating alternative proposals for waste management. They also coordinate activities such as international, national and regional meetings and conferences, marches, and other events to raise public awareness.

In the last 15 years, many protests and clashes with authorities have taken place. Below follows a brief overview of some of the key events occurring in Campania surrounding the management of waste management facilities and decision-making processes.

.

Dioxins in Campania

Spring 2002 saw the implementation of the so-called “dioxin alarm”, with the discovery of above-normal concentrations of dioxin in bovine and ewe milk during analyses carried out by a national Ministry of Health programme of food and environment monitoring.

At the beginning of 2008, the Campania Region commissioned the Sebiorec Study, to be carried out by the Superior Institute for Health, the Clinical Physical Institute of the National Research Council, the Epidemiological Observatory, the Naples Tumours Register, and 5 Campania local health offices) which saw the analysis of blood (780 persons) and maternal milk (50 women) samples for presence of dioxin and heavy metals. Samples were taken from 13 municipalities with various grades of environmental risk in the provinces of Naples and Caserta.

In most countries dioxin contamination is linked to industry, but in Campania it is mainly linked to the incineration of waste, legal and illegal. Human exposure to dioxins occurs through inhalation, skin absorption and food consumption, especially meat and dairy products. Airborne transport of dioxins and deposits in soil contaminate grass and plants that are ingested by livestock. Through the consumption of contaminated meat or other animal products, humans absorb dioxins through the gastrointestinal tract, which are diffused through the body, accumulating particularly in the liver and in body fat.

Dioxin contamination in Campania affects especially rural areas where a significant amount of food is produced, not only for local but also for national and international consumption.

The Campania 0 Waste Movement, composed of two main networks, the Health and Environment Campania Network (Rete Campania Salute Ambiente) and the Regional Campania Waste Coordination (Coordinamento Regionale Rifiuti della Campania) is now struggling for a new, and drastically different Waste Management Plan, one that is participatory, agreed by consensus, controlled by communities concerned with public health, and opposes incinerators and mega-landfills. These networks meet in assemblies and have scientific committees and thematic groups addressing issues and formulating alternative proposals for waste management. They also coordinate activities such as international, national and regional meetings and conferences, marches, and other events to raise public awareness.

In the last 15 years, many protests and clashes with authorities have taken place. Below follows a brief overview of some of the key events occurring in Campania surrounding the management of waste management facilities and decision-making processes.

.

Salient moments of mobilization

- The struggle against the construction of the Acerra thermovalorizor

Local committees evolved in opposition to the construction of the incinerator and in favour of more sustainable waste management, aiming to preserve an area already heavily impacted by waste and industrialisation. On the 29th of August 2004 a popular protest against the project was met with violent repression by both the police and army, profoundly affecting the local and regional movements and creating an atmosphere of fear among the local population. It became a symbolic moment illuminating the government’s institutional rigidity and willingness to resort to violence toward civil society demands for participation in waste management. It was also a key event in uniting local committees and organisations at a regional level. After years of struggle, the thermovalorizor was inaugurated on March 26th 2009 and authorised to burn any type or quality of waste, whether it adhered to norms or not, from ecoballs to unpacked waste.

.

- The Pianura battle

The Pisani landfill in Pianura (in the province of Naples) was in use for over 50 years and closed in 1996 due to its saturation, suspected violation of norms, and the dangers it posed to the environment and human health. The sanitation of the area was planned, but never implemented. During the last “waste emergency” in January 2008, the authorities reopened the landfill to receive waste for stocking until the completion of the Acerra thermovalorizor, where it was to be burnt. In reaction to the re-opening, the local population mobilised only to be violently repressed by police. Local committees, associations and activists involved magistrates however, and the landfill was sequestered on the 21st of January 2008. Enquiries into health issues and groundwater contamination led to the closure of the site as the impacts on illnesses were investigated. The landfill never did reopen and the so-called “Pianura Battle” became a symbol of victory for civil society mobilisation.

.

- The Acerra-Napoli March “The March of 1000 Yeses”

The adoption of Decree 90 in May 2008 announced planned infrastructural works and waste management measures that would threaten the entire region. In response, a march was organised for the 21st of June 2008 from Acerra to Naples for “Environment, Justice and Democracy”. The point of the demonstration was to draw attention to civil society demands for inclusion in consultations for the management of their territory. It also helped unify all of the committees and associations struggling for civil society participation and more sustainable plans for waste management.

.

- Uttaro

Uttaro in the province of Caserta has one of the most dense concentrations of landfills in the region. It is a small area with a population of about 200 000, and has been severely impacted by irresponsible waste management (Figure 13). Until the 1990s there was just one landfill (Migliore Carolina) with a capacity of 2 000 000 m3, and by the end of the decade two other smaller landfills were operating in the area. With the most recent waste emergencies two further sites were opened, another landfill was created overnight in 2005 and a new transit storage site designated, until it was later sequestered. A cave in the area of the Uttaro site found to contain illegal waste was scheduled for sanitation under regional plans in 2005, but in November 2006 authorities decided to use the site as a landfill and planned for its extension, leading to civil society mobilisation and the creation of the Waste Emergency Committee. For 3 days in April 2007, this Committee occupied the land and blocked the transit of trucks until they were forcibly removed by police. The land was then militarised to “guarantee the function of the plants”. The Committee continued its action however through a penal accusation and a legal appeal on the grounds of severe mismanagement of the site. On August 3rd Judge Como ordered the closure of the site due to its high concentration of toxic substances. This was another victory for civil society mobilisation, but 8 million t of waste are still concentrated in the area.

.

Figure 13: Buried landfill from the Uttaro dumpsite, showing obvious non-conformity (leachate and a broken chimney for gas expulsion) to safety requirements (Source : A Sud)

.

5.1. The conflict as a Post Normal Science problem

Campanian committees and associations have over the years developed robust alternative waste management proposals. However, despite their efforts to engage authorities and other official sectors in these processes, authorities have resisted debating alternative approaches to waste management, instead marginalising the participation and knowledge of organised civil society.

.

The Campania Movement critique of the existing waste cycle and its goal of energy recuperation, and its alternative proposals is based on two key principles of the 0 (zero) Waste concept: first, the reduction of waste production and implementation of door-to- door sorted waste collection; and second, the transformation of existing waste treatment plants, both compost and RDF facilities, into recycling centres using new technologies. This approach would reduce the need for incineration and would increase the recycling of materials (Movimento Campano rifiuti zero, 2009; Coreri, 2009).

.

In this sense the Campania waste conflict is an example of a Post Normal Science problem (D’Alisa et al, in press), where “facts are uncertain, values in dispute and decisions urgent”. In such contexts, a technocratic approach alone cannot address the complexities involved. Landscape values, traditional land uses, environmental justice claims, local values and interests and community rights to participate in local decisions on a range of issues at stake, point to the need for a different approach. Moreover, local knowledge and competences have much to contribute to the understanding of the conflict, and need to be considered. During the conflict the Campania Zero Waste Movement has shown the capacity of civil society to assimilate expertise and produce knowledge. By applying their activist knowledge and engaging in the practice of popular epidemiology in their struggle, Campania’s citizens have become specialists on issues such as health, land contamination, and waste treatment technologies, accumulating and assimilating specific knowledge, for example in relation to dioxins, environmental contamination, incineration, and waste collection and treatment, in order to formulate and construct alternatives.

The movement also denounces the way in which the Government has used the “emergency” to favour financial and private interests with public money, and exposes complex interrelations between political figures, and economic and mafia powers. Efforts to communicate these interrelations have been stifled in mainstream media, which works to misinform and manipulate public opinion. In the last emergency, the movement was criminalised by measures such as the militarisation of waste sites and protests, and the implementation of new laws condemning resistance organisers and demonstrators.

.

5.2. Emergency management and abuse of power

The above mentioned measures represent a clear attempt to undermine civil rights, and part of a wider process of legal reform directly linked to the waste emergency. Waste management has in fact been characterised by the abuse of power in at least two ways: through derogations of the law leading to the violation of numerous basic environmental and civil rights, and through continued application of the financial model used by general contractors.

.

Legal framework

The emergency has provided justification for the redesign of the legal framework related to waste management at the regional level. But other national legal provisions have been responsible for encouraging unsustainable waste management. The Italian CIP 6 Law adopted in 1992 for example favours the production of electricity through renewable and “assimilated” energy with public money. This latter category refers to any energy production method based on energy recuperation, like incineration. Producers can sell the electricity at a higher rate than that of non-renewable sources and the difference in price is paid by a tax that every citizen pays on their electricity bill.

The objective of this law was to encourage energy companies to orientate their production towards renewable energies, such as wind and solar, and at first glance, it seems quite “green”. Upon closer inspection however, in practice CIP 6 has enabled increased production of mainly “assimilated” energy, specifically, from incineration, favouring the construction of RDF plants and incinerators in the country. Paolo Rabitti in his book Ecoballe estimates that in 8 years, 453 million € was invested in ecoball production in Campania owing to CIP 6. Moreover, CIP 6 was recently extended to apply to the construction of 3 incinerators in Campania (Acerra, Santa Maria la Fossa e della provincia di Salerno) because funds could not be raised from private investors.

.

European infringement procedures

The European Union began infringement procedures against Italy for the implementation of CIP6 and against the Region of Campania for its waste management procedures. Regarding CIP6, there have been two separate procedures against Italy: Procedure n. 2004/5061 for the poor implementation of the European directive on renewable energy and for failing to introduce specific norms; and Procedure n. 2004/4336 for the misinterpretation of European norms through which Italy has implemented non- renewable sources of energy (incineration) as renewable ones. The procedure against Campania for its procedure for waste management is expected to lead to economic sanctions only.

.

The financial model of general contractors

Currently in Italy, major public works are carried out under the General Contractor and Concessionaire Model, a practice that was established under the fascist regime of earlier times. The so-called “Legge Obiettivo” law, passed in December 2001, set out procedures and modalities for funding large strategic infrastructure projects in Italy from 2002-2013. The official objective of the law is to ensure the most economical and rapid construction possible for public infrastructures, and to define the terms and conditions of private Entrepreneurs’ and their central role in all phases of public works organisation.

The “Legge Obiettivo” through various decrees and derogations favours a financial and management system based on unlimited sub-contracting, which translates in practice into the award of tenders as quickly as possible to the lowest bid, regardless of controls (even though these are usually laid out by project managers, as in the case of incinerators in Campania), security, public domain competencies and duties. This ultimately results in increased criminal infiltration and behaviours and the denial of basic rights.

This normative context is largely the product of the employment of substitutive powers, such as those applied by the Extraordinary Commissariat in times of emergency and crisis. The State of Emergency became an excuse for new development plans, which were ultimately defined by the private sphere, the sphere that stood to gain the most from these plans, to the disadvantage of the general public and public administration bodies. The result has been the complete disempowerment of the public domain: social development is now ruled by the private sphere that is able to pursue its own interests by using extraordinary powers that infringe laws. In this way local institutions are able to avoid real development questions and civil society resistance can be repressed with legal (and physical) threats.

On December 17th, 2009, the Council of Ministries voted on a new decree which effectively ended two states of emergency; the Aquilla earthquake and the waste crisis in Campania, and marked the return to normal practices from January 2010. For waste in Campania this has meant continued work on waste infrastructure development (including the Acerra incinerator) is back in the hands of local authorities still under investigation by the courts.

The decree also transformed the public body of Civil Protection into a private company, deeming it a”private subject, in its institutional profile and in the procedure for tenders and acquisition of goods and services”: ‘Protezione Civile Spa’. Board members of the company will be nominated by the Council of Ministries giving the President of the Council all decisional power both in private and public sectors for emergency management. This decree was voted on without any parliamentarian or public debate and with no media attention (Vegni, 2009).

.

5.3. Corporate Influence and Interrelations: The Role of Impregilo

Based on facts emerging thus far in the current trial, it would seem obvious that the Impregilo company, leader of the FIBE-Impregilo consortium that has run Campania’s waste management for the last decade, bears significant responsibility for the waste crisis. The national context helps to illustrate the issue at stake: the Cavert consortium, of which Impreglio controls 75%, was in charge of construction of the High Speed Train Line (TAV) between Milan and Florence. In March 2009 Alberto Rubegni, President of the consortium was fined about 150 million € and given a 5 year prison sentence for illegal waste dumping beneath the TAV rails. It cannot really be seen as a coincidence that the President of a consortium dominated by a company active in illegal waste management activities should be so implicated.

It is no less than bizarre however that the same man, Rubegni, despite having been convicted, is currently serving as administrator of Impregilo for the construction of the Messina bridge. This project that will connect Sicily with the continent has become the source of a new environmental conflict in southern Italy, and is furthermore seen to be at high risk of mafia infiltration. Critics maintain that the construction of this bridge does not correspond to any real transport need, and that the project will generate much debt for future generations. Rubegni announced in September 2009 that work on the bridge would begin in January 2010.

Not only in Italy is Impregilo active. Besides building seemingly unnecessary bridges, toxic train lines and managing waste well enough to create “emergencies”, the company is also very active abroad. Among its many projects, Impregilo has built hydro-electric facilities in Nigeria, Lesotho, Kurdistan, Turkey, Argentina, Guatemala and Nepal. In July 2009, Rubegni announced that Impreglio, leading the “Grupo Unido por el Canal” consortium, was awarded a significant tender for construction on Panama Canal (Lonardi, 2009).

.

5.4. Corruption and Ecomafia Infiltration of Urban and Industrial Waste Management

The gravity of the Campania waste issue is the result of a combination of shortcomings in systems of control, in public policies and their implementation. For Legambiente, (the Italian environmentalist NGO), Campania’s waste management system was developed on the basis of the four “I”s: illegality, inefficiency, irresponsibility and indecision. The role of the Camorra and widespread corruption in creating this situation cannot be underestimated.

.

Ecomafia

Directly linked to corruption, the ecomafia as previously mentioned, are criminal organizations that commit crimes causing environmental damage. These are the most problematic actors in Italian environmental criminality, and the region of Campania is where they are most active, particularly in waste management. Legambiente estimates that the national illegal waste market from 1995 to 2005 was worth 26.6 billion €. In the year 2007 alone, the illegal hazardous waste market generated 4.432 billion € and investment by mafia in urban waste management was estimated at 963 million €. Between 1998 and 2007, there were almost 3000 waste related-crimes, corresponding to an incidence of 0.2 per km2 (Legambiente 2007, Legambiente 2008).

.

Illegal waste flows

The main north-south axis of waste flows is divided into an Adriatic route going to Puglia, Abruzzo and Romagna and a Tyrrhenian route going to Campania, Lazio and Calabria. However, the dynamics of waste traffic are continually changing, and from Campania, the trade has spread to “clean” zones like Basilicata and Umbria. Another recently developed dynamic is the flow of waste from Campania to the north, across the regions of Emilia Romagna and Lombardia and through the Milano Como axis, to arrive in Piemonte.

It is estimated that in the last 5 years, 3 million t of all types of waste have been illegally treated on the Tyrrhenian route, 1 million t of which was treated in the province of Caserta alone. Increased police control (ironically) and the exhaustion of landfills have contributed to the emergence of these new routes. Ecomafia waste activities are not only regionally and nationally based. They also have an increasingly international dimension: investigations focused on 2008 revealed traffic in thirteen countries including Austria, France, Germany, Norway, China, India, Russia, Syria, Liberia and Nigeria (Legambiente, 2005, 2007, 2008).

.

5.5. Waste production and treatment

The paradox of the situation in Campania is that the region actually produces less waste urban and hazardous waste than the rest of the nation on average, although it would not seem so in the light of repeated crises. This is due to the fact that the illegal waste trade attracts waste from outside the region, although it also makes some “disappear”.

A lack of data on treated waste makes the accurate assessment of waste production and treatment in the region difficult, but available data (see Table 1) on the amount of waste produced per capita, the amounts of sorted urban waste (SUW) and the price of treatment in Campania compared to the rest of Italy illustrates clearly that waste management practices do not score well in terms of their environmental friendliness.

.

Table 1: Waste production and treatment in Campania and Italy

| Campania | Italy | |

| Kg waste / Per capita | 485 | 539 |

| % SUW | 10.6 % | 24% |

| Price of treatment / kg | 0.03-0.04€ including transport | 0.04€ excluding transport |

.

Moreover, in 2004 Campania produced 4.3 million t of hazardous waste (below the national average) of which only 2.6 million t was treated in the region. This can be explained by two factors: first, the absence of binding norms for the treatment of hazardous waste in its region of origin; and second, the national phenomenon of “ghost waste” (source: Eurostat, Apat). Ghost waste refers to waste produced but not treated legally. It is one of the only indicators of illegal waste treatment as it is difficult to quantify the real amount of such traffic. While there are no reliable regional indicators of ghost waste due to lack of data, it has been estimated that in 2008 31 million t of hazardous waste vanished, the equivalent of a mass 3 hectares wide and 3100 meters high.

.

5.6. Causality, consequences and responses

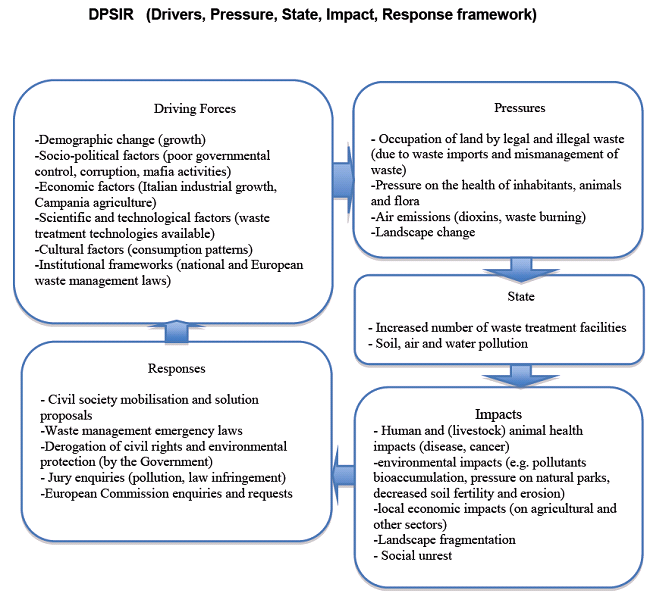

DPSIR (Drivers, Pressure, State, Impact, Response) is a classificatory device that enables the study of environmental indicators in order to explore causality (drivers, pressure), consequences (state, impact)

Figure 14: DPSIR of Waste in Campania

and responses to a given environmental issue. When the Campania waste conflict is structured according to the DPSIR model, it highlights the underlying causes and current consequences of the waste management policy adopted there. This model is based on the assumption that there are causal relationships between the different elements of the socio-environmental system.

In the case of Campania (Figure 14) , the Drivers, i.e. the social, economic and institutional systems, directly and indirectly trigger Pressures on the environment and society and as a consequence their States change, through the accumulation of waste without proper control and treatment. The Drivers have been the production of waste by the economic system, together with the existence of defective socio-political institutions. The production and displacement of waste puts Pressure on the local environment in Campania. Its State changes. These changes have Impacts on humans and the environment, for instance water pollution, the occupation of land, health deterioration. These in turn lead to social and policy Responses. The Responses themselves can become further causes of Pressures on the environment (e.g. incineration is a response that might lead to production of dioxins).

The DPSIR framework in this way offers the potential to clarify and organise the elements of the waste conflict in Campania, shedding light on its complexities and enabling a more thorough assessment of the full range of issues at stake.

.

Figure 14: DPSIR of Waste in Campania

.

.

5.7. Campania as a case of Environmental Injustice

The waste crisis in Campania is an example of extreme mismanagement of a basic public service, but another striking dimension of this case is that it also clearly represents a situation of severe environmental injustice. In Campania, the burdens of waste and contamination and the presence of environmental criminality are unequally borne by the residents of this region. These citizens, many of whom live in poverty are the most affected, as this paper has demonstrated. The persistent exclusion and repression of Committees and civil society very clearly represents a denial of rights of self-determination’s and popular participation processes. Moreover, the links to economic benefits enjoyed by the Camorra, policies and regulations such as the decrees and plans implemented in the course of the waste emergency, and communities’ lack of power are obvious.

.

Lawrence Summers’ principle on waste and poverty in Campania

Lawrence Summers, current Director of the White House’s National Economic Council for President Barack Obama, applies to waste and polluting activities the principle of comparative advantage. In 1992, Summers was Chief Economist of the World Bank and wrote an internal memo arguing that pollution should be sent to places where there are no people, or where the people are poor. In his own words:

“the measurements of the costs of health impairing pollution depends on the foregone earnings from increased morbidity and mortality. From this point of view a given amount of health impairing pollution should be done in the country with the lowest cost, which will be the country with the lowest wages. I think the economic logic behind dumping a load of toxic waste in the lowest wage country is impeccable and we should face up to that” (mek1966.googlepages.com/summers.doc).

.

From a strict economic analysis these conclusions are correct, however, this is to the exclusion of any non-monetary considerations such as impacts on health and environmental externalities. The Campania waste crisis illustrates the Lawrence Summers’ principle on both regional and national levels. Regionally, direct links between poverty and contamination are apparent, particularly for the provinces of Caserta and Naples, where as we have shown there are direct links between sites of contamination and economic disadvantage. From a national perspective, Campania is one of the poorest regions in Italy, where 21% of families live below the poverty line. In 2003, the regional average wage per capita per year was around 11.000 €, approximately half the national average. Campania also has a low education level, with only 15% of the region’s population between 15 and 52 years having completed compulsory education in 2001. In Campania life expectancy is also below the national average especially in the provinces of Caserta and Naples (Table 2).

.

Table 2 : Life expectancy in Italy and Campania, (Source: Istat 2006)

| Campania | Italy | |

| Men | 76.91 | 78,44 |

| Women | 83,5 | 83,97 |

.

The answer to the ethical question of whether it is acceptable to subject poor people to health and environmental contamination for economic gain should be obvious, but it seems that in practice, adherence to the Lawrence Summers’ principle is behind much environmental crime and injustices.

.

Addressing environmental crime and injustice

Legambiente estimates that 15.6% of Italian criminality is environmental. In most cases, like in Campania, such crimes are not isolated but part of a broader context of systemic environmental injustice. One of the main battles of defenders of environmental justice is the effective punishment of environmental crimes through the implementation of an effective preventive and regulatory framework that goes beyond the occasional enforcement of monetary fines.

Monetary compensation and fines are high stakes, and highly contested issues when applied to contamination of the environment and human health. Recently, the extreme right party (La Destra) submitted a request to the European Court for Human Rights for compensation for citizens affected by waste emergency procedures of 2008. The Italian state has been ordered to pay an average of 1.500 € to citizens suffering economic, biological and living quality damages. The details have still to be published and the Court will meet with the Italian government to decide on how to implement compensatory measures in practice, but in the context of broad impunity and social injustice, it is absurd to believe that monetary compensation of 1.500 € per person can possibly compensate for the destruction of an entire agrarian economy, the lives of the dead, the health of future generations and for the devastating of contamination that is sure to have an impact for decades to come. The limits of monetary compensation for environmental contamination without justice or any real political effort to protect ecological services are blindingly obvious in the context of the Campania waste crisis.

.

Figure 15: Chiaiano citizens and committees against the landfill in Chianino (Source: Carta)

.

The European Union is pursuing an infringement procedure against Italy for the waste crisis in Campania, which will lead to the payment of a fine by the State but will not see the condemnation (legal or even symbolic) or prosecution of the individuals, public bodies and companies responsible for the crisis. There is hope however that with national level implementation of the EU’s Nassauer Directive on penal sanctions for environmental crimes adopted by the European Parliament and the Council of the European Union in November 2008 (Directive 2008/99/EC), this situation could change.

.

Environmental crimes in Italy should be prioritized as national and European concerns. There are 71 “eco-crimes” every day in the country, or 3 every hour, half of them in Calabria, Campania, Sicilia and Puglia, the four main regions of mafia activity. The Campania waste crisis, has so far cost an estimated 1.8 billion € (Legambiente, 2009) and the current panorama gives little hope for concrete improvement.

The waste treatment strategy adopted by government has only addressed the symptoms of the crisis (the accumulation of ecoballs), rather than the roots of the crisis. These are to be found in: a lack of participative democracy, an absence of research, the need for behavioral change, necessary improvements to the judiciary and control efforts, and implementation of effective dissuasive and penal sanctions. Moreover, the “extraordinary” handling of the crisis has raised some extraordinary questions: How have companies and public administrations been able to under-declare quantities of produced and treated waste without any consequences? How can the damages suffered in Campania have gone unnoticed? How could the collusion of controlling public bodies not have been suspected with so much evidence of corruption, mafia infiltration, easy money and vested interests? Perhaps contamination of the territory is the necessary price that local inhabitants have to pay for their proximity to a lucrative and attractive industry.

Civil society committees and organisations have so far been excluded from waste management and decision making processes through the use of repressive measures and military interventions. As an act of goodwill government authorities need to recognize their obligation to create space for true civil society participation, rather than continuing to make disappointing, sporadic and instrumental promises that only create the illusion of participation.

Uneven availability of scientific data makes it difficult to prove that toxic substances in the air, soil and water of Campania due to waste contamination are causing serious health impacts. While such a conclusion may seem like common sense to most, the mafia are able to maintain that contamination is the result of industrial activity. Further scientific research is needed for the production of accurate figures of waste production and treatment, and for the construction of a clear analytic framework to assess the current level of contamination and related risks. This fundamental step is necessary if the issue is to permeate the consciousness of the general public.

The media and the government have had a major role in convincing public opinion that things are now back to normal, justifying abuses of power by government through emergency measures and concealing the continued use of improper waste management practices. Remarkably, instead of learning from past errors and looking for improved and alternative models of waste management, the government is continuing its promotion of outdated technologies such as RDF and thermovalorization in the southern regions of Sicily, Calabria and Lazio.

With regard to waste management then, Italy is positioning itself to repeat its mistakes. If, as we believe, the problem is rooted in mafia activity, corruption and profit interests, diversion from the current path will require major efforts to be put into improving judicial investigations, police control of the territory, and penal prosecution. If the citizens of Campania are to succeed with their demands for environmental injustice, these fundamental steps must be taken. Furthermore, the co-operative efforts of civil society, the research and legal communities and policy-makers will also be required to create the necessary conditions for the development an appropriate legal framework to prevent future violations of environmental justice.

.

.

APAT, ONR (2006), Rapporto rifiuti

Arpac Campania (2008) Siti contaminati in Campania

Comitato Emergenza Rifiuti, Lo Uttaro: una bomba chimica per 200.000 persone, 2009

Commissario Delegato per l’Emergenza Rifiuti nella Regione Campania, Piano Regionale Rifiuti Urbani della Regione Campania ai sensi dell’art. 9 della legge 5 luglio 2007, n. 87

Coordinamento Regionale Rifiuti, Proposte del Coreri, 17 febbraio 2009

D´Alisa, Giacomo, David Burgalassi, Hali Healy, Mariana Walter, Campania´s conflict: waste emergency or crisis of democracy? (in press), Methods and Tools for Environmental Appraisal and Policy Formulation, Proceedings of the 3rd THEMES Summer School, Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Caparica.

Danno rifiuti, 1500 euro a testa. La Corte Europea : “lo stato risarcisca I cittadini campani”, R. F., la Repubblica Napoli, 20-06-2009

De Crescenzo D., “La truffa dell’emergenza rifiuti. La compagnia delle ecoballe”, Narcomafie, Luglio-Agosto 2007, www.narcomafie.it/articoli_2007/art2_7_2007.htm

DECRETO-LEGGE 23 maggio 2008 , n. 90 – Misure straordinarie per fronteggiare l”emergenza nel settore dello smaltimento dei rifiuti nella regione Campania e ulteriori disposizioni di protezione civile.

Paolo Esposito, Napoli – Riapre la discarica a Pianura, caffénews, 5 Gennaio 2008 di http://caffenews.wordpress.com/2008/01/05/napoli-riapre-la-discarica-a-pianura/

Iacuelli A. (2007), Le vie infinite dei rifiuti. Il sistema campano

Iacuelli A., “L’impresa mostro”, Carta, Anno XI, n.15

Ispaam-Cnr, Discariche in Campania: in pericolo la catena alimentare, 11 Maggio 2007, http://www.cnr.it/cnr/news/CnrNews?IDn=1650

Antonio Pastena, Analisi e Riflessioni di un chimico campano da venti anni sul campo, 2008, http://ambienti.wordpress.com/testi/la-chimica-dei-rifiuti-campani/

Legambiente, Osservatorio Ambiente e Legalità (2001), Rapporto Ecomafia 2001. L’illegalità ambientale in Italia e il ruolo della criminalità organizzata, Roma

Legambiente, Osservatorio Ambiente e Legalità (2007), Rapporto Ecomafia 2007. I numeri e le storie della criminalità ambientale, Edizioni Ambiente, Milano

Legambiente, Osservatorio Ambiente e Legalità (2008), Rapporto Ecomafia 2008. I numeri e le storie della criminalità ambientale, Edizioni Ambiente, Milano

Legambiente (2008), Dossier “Rifiuti Spa”, Dentro l’emergenza in Campania: i numeri e le storie di un’economia criminale

Legambiente (2005), Dossier “Rifiuti Spa”, Radiografia dei traffici illegali

Legambiente (2003), Dossier “Rifiuti Spa”, I traffici illegali di rifiuti in Italia, Le storie, i numeri, le rotte e le responsabilità

Legambiente (1995), Dossier “Rifiuti Spa 2”. Secondo libro bianco di Legambiente sullo smalitimento illegale nel mezzogiorno dei rifiutti urbani e industriali prodotti in Italia

Legambiente (1994), Dossier “Rifiuti Spa”. Libro bianco di Legambiente sullo smalitimento illegale nel mezzogiorno dei rifiutti urbani e industriali prodotti in Italia

M. Menegozzo, F. Scala, M.T Filazzola, A. Siciliano: Rischio diossine in Campania, Dati e Prospettive, Arpa Campania Ambientale n.2, February March 2008